Chapter 2.

|

| person-oriented (a/b) and | |

| environment-oriented (c/d): |

Mastering more general demand-structures depends to a great extent on

the ability to act competently, as well as the availability of social

resources, which represent

[27]

the decisive determinants of healthy vs. pathological personal

development.

Hacker (1998) defines an act as the

"smallest unit of intentional, directed activity." (pg. 67)

It is directed by rational processes of information assimilation and is goal-oriented.

Lantermann & Schröder (1991) also consider, moreover, actions' emotional and unconscious course-processes.

Hacker (1998) distinguishes between three hierarchically-constructed levels of action-regulation

| (operation, | |

| action, | |

| activity). |

Activity represents the most general regulatory level, which is affected by a person's motive-structure (overarching goals and needs).

The concept of "activity" (Leontjew, 1979) is a very elastic construct and functions as a broader conception of general human psychological regulatory activity, which in its operation follows a dialectical ring-structure. From a personality psychology perspective, it can be characterized as a "macro-process of the life-course." (Schröder, 1991, pg. 171)

Although the activity [*] follows essentially the same operational structure as the act [**], it goes beyond it, because it lays down a relationship between human beings and the environment.

[* "Tätigkeit"]

[** "Handlung"]

No motive-structures may be inferred from individual acts.

Based upon the conceptual framework of operational psychology, the capability to act competently is present when an individual is repeatedly successful, via the activity, in neutralizing the contradictory quality of the relationship between the person and the environment. In addition to that, the environmental conditions are transformed and adapted to a person's psychological structure (appropriation) or status along the lines of an adjustment to the demands of the environment (reflection). This process of transformation manifests itself in terms of outcomes (concretization).

This same process is described in Piaget's (1976, 1983) theory of mental development in terms of the concepts of assimilation and accommodation. It also follows the dialectical assumption of an interplay between tension and the dissolution of tension (Piaget's "equilibration") and comes very close to the principles underlying activity theory, without, however, being identical to it. Operational theory places the emphasis on the regulatory cycle (goal-action regulatory loop). These are described in detail in Hacker's (1998) general theory of action-regulation. As micro processes, however, they are not the subject of this study.

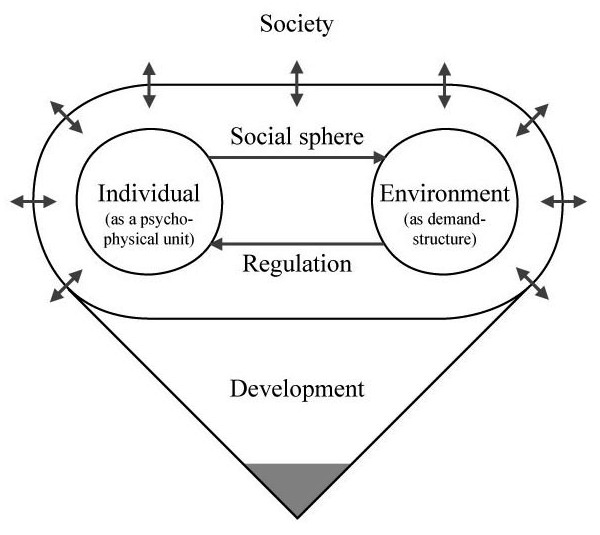

The successful dissolution of the tension between the individual and the environment via action is what makes development possible, because this is how the individual establishes room within which to live (Lewin, 1963), to meet his or her needs for space and fulfillment. The individual-environment relationship is depicted in Fig. 2.

[28]

In the behavioral psychology's conceptual framework, the active individual is emphasized. By activity it is meant that one is responsible for generating one's own stimuli, meeting one's own demands, and setting one's own goals.

The individual also has an independent, active role in

| mastering critical life-events (Filipp, 1990) or | |

| normative developmental tasks (Havighurst, 1982). |

Havighurst defines a developmental task as

"a task which is placed before an individual during a particular period of life. Its successful mastery leads to happiness and success, whereas failure makes the individual unhappy, leading to rejection by society and difficulties in mastering subsequent tasks." (pg. 2)

The potential consequences for identity development of the non-mastery of developmental tasks are described in the classic theories of Erikson (1948) and Marcia (1966).

The concept of identity is closely related to that of self-concept, with the two often being used interchangeably. (Oerter & Montada, 1995)

In Krupp's (1989) more contemporary theory of identity, the development of partial identities ("patchwork identities") is emphasized. This had evolved as a sensible means of finding one's way in the ever-changing environmental conditions of the jungle, and thus also,

"in the completely normal chaos of love." (Beck & Beck-Gernsheim, 1990)

Under the conditions of modern industrial society,

"the personal formation project of 'personality' has become an ongoing task for every stage of life." (Schröder, 2002, pg. 227)

In terms of behavioral psychology, this universal process can be expressed as follows: If a person is not successful in mitigating the inherent conflicts between the self and the environment, he or she will come under pressure and stress. The "metabolic process" between person and environment is distorted, thus – as a rule – setting in motion act-regulating efforts to compensate for it, with the goal being self-stabilization. (Schröder, 1991)

Jantzen (1979) characterizes the distortion of the personal-environment relationship as isolation, the sources of which could be diverse

(e.g., toxic, traumatic, or infectious agents, disturbances in social relationships, restricted living conditions).

Isolation is, in turn, characterized by a distorted apprehension of objective reality. Over the long-term, this leads to destabilized activity-regulation (diminished life-mastery competency) and faulty, pathogenic development. With the concept of isolation, the focus of attention moves to the relationship between human beings and the environment.

Intervention action must, from a behavioral psychology perspective, be aimed at eliminating the internal and external conditions that lead to isolation. (Schröder, 1988)

Uncovering and overcoming the conditions that bring about a distorted correlation between the individual and the social environment goes beyond the realm of counseling and therapy and touches on collective social interests. The specifics of the respective tensions and the possibilities for their resolution depend centrally on social circumstances, and in particular on a society's average level of evolved consciousness. (Wilber, 2002)

According to Becker (1982, 1992, 1995), health and disease are consequences of individual efforts to master internal and external demands.

| Health and well-being are the expression of a person's positive success-balance of individual regulating conditions. | |

| Illness and disease, on the other hand, are the result of a negative success-balance. |

The experience of personal meaning and positive emotions are, as a rule, significant indicators of an individual's successful negotiation of the tensions inherent in one's relationship with the outside world. According to Schröder (1991, pg. 179), health can be characterized

"as the successful compromise between environmental demands and one's own need and motive structure, such that a functional optimum is attained."

According to Antonovsky's (1979, 1987) saluto-genetic model of health,

it is understood as a process of ongoing interplay along the lines of

regulatory activity. Health and disease are, in the saluto-genetic

paradigm, not dichotomous – as

[29]

in the patho-genetic approach – but

rather, can be represented in terms of a continuum. The crucial

determinant of one's position on the so-called "health-disease

continuum" is the regulatory activity's efficiency in dealing with

stressors.

Fig. 3

|

A person's state of health is determined, again according to Antonovsky (1979, 1987), by an individual's basic attitude toward the world and his or her own life, which Antonovsky characterizes as the "sense of coherence." This global construct represents the essential individual magnitude of psychological influence on a human being's state of health and disease. (Bengel, Strittmatter & Willmann (2001)). The sense of coherence manifests the extent

"to which someone has a deep, lasting, but nevertheless dynamic sense of confidence where,

[1] in the first place, demands from both the interior and exterior experiential worlds are integral to one's life-course, predictable, and explicable and where,

[2] secondly, the necessary resources in order to meet those demands are available. And

[3] third, that these demands are challenges that merit investment and engagement."

(Antonovsky, 1993, pg. 12)

The development of a strong as opposed to a weak sense of coherence depends, above all, on whether generalized psychosocial conflict-resources (major psychological generalized resistance resources) are in place that are tied to social realities. These include, according to Antonovsky (1993),

| knowledge, | |

| intelligence, | |

| flexibility, | |

| material resources, and | |

| social support. |

These kinds of resources are effective in all situations, and enhance a person's psychical ability to cope with demanding situations.

Antonovsky's central saluto-genetic constructs are included in Becker's (1992) interactional demand-resources and mental health models

(Becker, 1982, 1985; Becker & Minsel, 1986).

Both models follow the tradition of the stress-mastery paradigm and adhere to the behavioral psychology conceptual framework.

The importance of the demand-resources model lies in the fact that it explains the bond between health and everyday life. Becker has sketched out a health model which is not characterized by the absence of disease. Health is influenced by and comes about via

"a subject actively regulating his or her environment while simultaneously being shaped by it" –

depending on social realities. (Becker, 1995, pg. 199) Figure 4 provides an overview.

Becker's [*] interactional demand-resources model

[* 1992, p. 71]

Becker differentiates between mental health as state and mental health as quality. Mental health as personal quality is defined by Becker (1995) as the enduring "ability to master external and internal demands." (pg. 118)

Mental health is interpreted by many authors as the sign of a realistic appraisal of the environment and one's own self. (See, e.g., Rogers, 1991) Health represents both the basis for and the result of adequate regulatory processes. (Becker, 1982)

Disease, by contrast, goes hand-in-hand with limited action-regulatory competencies, as Beck's theory of depression (1967) also makes clear.

Beck postulates three specific cognitive distortions in depressed persons, which he designates as the "cognitive triad." There is in depressives a negative view

| of the world (negative conception of the environment), | |

| of their own personhoods (negative self-concept), and | |

| of the future (negatively pre-adjusted conceptions of the environment and the self). |

This manifests itself in

the depressive assuming

[30]

a subjective lack of control over his

life-circumstances: He anticipates failure and therefore willingly

places the blame on himself, wrongly ascribing the ensuing result to his

own capabilities rather than chance or luck. Depression is associated

with a diminished sense of life, and a clearly elevated rate of suicide.

(Reinecker, 2004)

According to Reschke & Schröder (2000), stress is a human psycho-physiological readiness response-posture necessary for overcoming threatening, problematic situations. Therefore stress arises when the realm of personal tensions between demands, capabilities, resources, and personal values are thrown into dis-equilibrium and external and/or internal demands are no longer able to be met by the usual demand-routines. The individual makes a personal assessment that basic physical and psychological needs are under threat. According to Schröder (1996), these basic needs may be characterized as:

A person's competency to cope with stress is what decides whether the end result will be healthy or diseased development.

| Successfully

achieving the strived-for action-regulatory resolution of tensions

between person and environment is what, as a rule, is conducive to

self-development and to increasing the personality's degree of maturity [31] (development in the direction of health). | |

| Failure to achieve a

durable action-regulatory resolution leads to pathogenic situations,

which means the destabilization of both the self and the relationship

between the individual and the environment. (Schröder, 2001a, 2001b) |

Schröder (1996) distinguishes four stages in the destabilization of the human system under the conditions of heightened demands.

In the third and fourth stages of reaction-formation, what we are talking about is a person's inadequate yet purposeful attempts at stress-reduction. The disease-concept can be concretized as an

"objective events-process of escalating contradiction between psycho-physiological regulation and environmental conditions." (Schröder, 1991, pg. 179)

Disease is to be understood as a new regulatory quality which has taken shape under conditions of pressure owing to an individual's existing, insoluble conflicts. Disease is therefore a consequence, as per the above-described four stages, of inadequate mastery-competency relative to particular demand-structures. Disease represents purposeful behavior in that it fulfills important act-regulatory functions (albeit at a high cost).

Depression serves the primary function of providing the organism with a long- and urgently-needed respite. A secondary function of depression would be to put out an 'S.O.S.' call, which may be communicated via the expression of suicidal thoughts, which will result in increased attention from care-persons, friends, and relatives.

An individual's course through these four stages of increasing decompensation can extend over a period of years. Occasionally, there are even compensations in some life-areas. Diagnosable injuries to the psyche are, in the final analysis, the consequences of a distorted relationship between the individual and the environment, and are brought about by stressful experiences. (Schröder, 1996, Reschke & Schröder, 2000)

[32]

Schröder (2001b; 2002) portrays the essence of human regulatory activity in terms of two interrelated regulatory cycles. These are depicted in Figure 5.

Primary emphasis of human

regulatory activity

with subdivisions [*]

[* Schröder, 2002, p. 230]

The internal cycle pursues the goal

"of guaranteeing the individual's organizational structure and psycho-physiological integrity."

(Reschke & Schröder, 2000, pg. 48)

Capabilities for reflection and the regulation of emotion are very important for the stabilization of the self-system.

What is meant by emotional competence is that a person is able to cope with varying degrees of arousal and activity as well as different emotional qualities. (Also see Goleman, 1996.) A person must be in a position to obtain a sense of a euthymic state of affairs. (Schröder, 2001a)

An individual who has the ability to personally reflect on himself is reflexively competent. The readiness as well as the capability for reflexive activity vary markedly among individuals and depend on influences of differing magnitudes

(e.g., current life-situation, personal mastery style, emotional lability).

The external cycle pursues the goal of regulating the individual-environment system within the social context. This requires

| intelligence, | |

|

fact-competency (e.g., familiarity with the Internet), and | |

| social

competence (e.g., use and cultivation of social resources). |

It is due only to the presence and the complementary effectiveness of the two regulatory cycles that the constitutive prerequisites of life-proficiency and mental health exist. (Schröder, 2002)

Competent behavior is characterized by a person's successful mastery of the two activity tracks in an integrated form. Object-related results, for example, are – to a considerable extent – dependent upon internal regulation

(e.g., associations with dysfunctional thoughts).

General (mastery-) competency means the ability to

| meet one's own needs, | |

| get one's way, | |

| take in various influences, | |

| interact with other people, and | |

|

actively form interpersonal relationships. (Reschke & Schröder, 2000) |

In addition to social conditions and subjectively-experienced

social support,

[33]

self-concept, as a central component of the

personality, is another moderating influence on competent action. (Schröder

et al., 1984)

There are a large number of heterogeneous definitions of self-concept.

(Filipp & Frey, 1988; Filipp, 1993)

In the following, an attempt will be made to explain the conceptual definition of the act-regulatory-oriented notion of self-concept employed in this study. (Also see Greif, 1994.)

The self-concept is the consciousness-moderated representation of one's own personhood. It contains hierarchical information regarding one's own self, which a person has obtained on the basis of experience.

Schröder (1992) defines the self-concept as

"the central psychological notion of a human being's acquisition of information in the process of becoming conscious about one's self with regard to one's nature, one's individual peculiarities, and one's place in the social system and social context." (pg. 315)

In terms of content, the self-concept represents the sum total of every structured inventory of knowledge about and understanding of one's own person, along the lines of the formation of models. These are stored in long-term memory in the form of concepts or schema. (Schröder, 2002)

The essential contents of the stored knowledge are, from a behavioral psychology perspective, situationally tied to the capability-concept. Situationally-tied means, in the broadest sense, demand-related.

According to Schröder at al. (1984), the demand-related acquisition of the personal capability-concept is of greater value, compared to its non-specific acquisition, in predicting actual, observable behavior. General dimensions of personality such as neuroticism have no value in terms of explaining behavior and are static personality constructs. And they are often formulated tautologically

(e.g., heightened susceptibility to stress is caused by strong reactivity to stress).

The self-conception of social functioning potency represents an act-regulation-oriented, relatively broad construct that covers conceptions of capability and effectiveness in demand-situations. (Schröder, 1985)

Social or so-called interpersonal functioning potency is related to capability-structures which enable a person to actively take part in social demand-situations, influence the behavior of other people, and form interpersonal relationships.

Schröder (1985, 1992) emphasizes, in presenting his models for the capability-structure of interpersonal competency, that this consists of inter-personal act-competency and intra-personal self-competency

(see primary emphases of human regulatory activity).

Act-competency comprises both orientational and regulatory aspects.

| Orientational act-competency is present when the perception and representation of the environment is close to actual reality (= adequate environment-concept). | |

| Regulative act-competency encompasses operational ways of behaving (knowledge, techniques, strategies, etc.), by which varying degrees of influence are exerted on demand-conditions. | |

| Intra-personal self-competency involves the ability to regulate the emotions of, and reflect upon, one's own self. |

The presence of interpersonal functioning potency is a prerequisite for human beings' general ability to function in society. The self-concept has a dual function: It is both active in

| regulating social functioning potency as well as | |

| a reflection of one's own personhood. (Schröder, 1992) |

In terms of content, interpersonal functioning potencies represent broad social capabilities, such as

| the need and the ability to establish and form social contacts (communicability) or | |

| the ability to cognitively

and emotionally interact with one's conversational [34] partner (decentering and empathy). |

Even self-conceptions of social efficacy such as self-control and being conscious of one's control over the environment are part of social functioning potency. Consciousness of one's control over the environment represents the self-appraisal of one's own effectiveness in influencing and altering the environment. (Schröder et al., 1984; Schröder, 1995)

In depressed persons, who no longer see themselves as active agents but instead develop a sense of being at the mercy of circumstances, there is a deep disturbance in one's consciousness of environmental control. Consciousness of self-control also involves the ability to actually regulate and control reflected demands.

("I would have to act in such-and-such way... I will actually succeed in acting in such-and-such way.")

Self- and environmental-control consciousness are closely related to the construct "mental health."

(Schröder, 1985, 1999, 2003; Becker, 1992, 1995)

From a perspective of behavior-oriented personal psychology, "mental health," as a meta-construct of personality, may be split up into its constituent aspects of self- and environmental-control consciousness. By understanding these constituent aspects, it is possible to make conclusions regarding the nature of distorted activity-processes (internal vs. external regulatory cycles). That, in turn, will yield some indication as to precisely which conditions of isolation would have to be addressed through intervention in order to eliminate a distorted acquisition process. (Schröder, 1988)

According to Schröder (1985, 1992), the variables of communicability and environmental-control consciousness are particularly likely to merge with the ability-conception of "self-confidence." This is closely tied to the globally-assessed aspect of self-conception, the "sense of self-worth."

Whether there is a diminished or heightened sense of self-worth is strongly dependent upon the balance of one's own demand-standards and success achieved. Individual-oriented intervention approaches to regulating the sense of self-worth can be addressed to act-competency as well as demand-standards. Environment-oriented intervention focuses (in reference to marginal groups) on socio-political changes, aimed at integrating social minorities.

The special topic to be considered in the present study, as an additional and substantive aspect of functional potency, is that of the "sexual self-concept." (Snell, 1988)

This encompasses a given person's differentiable act-competency, efficacy, and experiences with regard to general human sexuality. In terms of their respective scopes, there is only a slight degree of overlap between the sexual self-concept and the more global self-reflected constructs of communicability, de-centering (empathy), and self- and environmental-control consciousness.

Included as a general motivational component of the self-concept is the construct of self-awareness. Filipp (1989) understands self-awareness to be an inter-individually varying, imprinted dispositional orientational awareness of one's own self. It can be subdivided into

| a private aspect (reflecting on one's own self) and | |

| a public aspect (reflecting on one's effect upon others). |

This construct is closely associated with observable behavior and therefore has great act-regulatory importance.

Self-concepts have not a direct but rather an indirect connection to observable behavior. Their functional aspect consists of the fact that they are instrumental in realizing competent action. (Petermann, 1984)

Self-schemas of social functioning potency, which are more or less positively imprinted are, therefore, act-effecting if a person refers to them when taking action. This requires a certain degree of self-awareness. Self-awareness comes into play when the congruence of need, situation, and psychical organization becomes distorted. (Seikowski, 1983; Petermann, 1984)

Information relating to one's self can potentially be called for in

all phases of act-processes. They serve a moderator function in

processes of the orientation towards, motivation for, carrying out, and

control over a given act. For example,

[35]

the self-conception of one's

general act-planning capabilities is important for calculating whether

one's own abilities are sufficient for a successful act-realization. (Petermann,

1984)

In interpersonal demand-situations, a person orients himself towards socio-political matters on the basis of

| one's attitude, | |

| previous information, and | |

| momentary emotional state. |

Environmental impressions get sorted out and represented cognitively (environment-concept). Environment-concepts and self-concepts interact closely with one another and have a major influence on the generation of complex conceptions of situations.

Going into the conception of the situation itself are

| value-orientations and | |

| the status of current needs. |

The person anticipates possible act-goals. The emotional state (self-esteem) and cost-benefit analyses play a large role in the decision-making process. As is the case with self-concepts, situation-conceptions have a direct, act-guiding function.

Successful act-implementation now depends on whether the appropriate information is able to be actualized. The situation-conception must harmonize with information that has been stored in long-term memory. What is decisive is

| the existence of an internal personality-model that comports with actual reality, as well as | |

| a realistic perception of the

environment. (Seikowski, 1983; Petermann, 1984; Schröder et al., 1984) |

According to Seikowski (1983), self- and environment-concepts can exert a regulatory influence on behavior in three ways:

| [1] The consequent effect of a markedly deficient

environmental-conception is that persons are unable to identify,

evaluate, and sort through information concerning interpersonal

demands. In addition this leads to the formation of inapt

situation-conceptions as well as ineffective act-outcomes (deficient

environment-conception). | |

| [2] Though a differentiated, situationally-adapted

environment-conception does exist, due to a generally negative

self-concept, the actualization of objectively present capabilities

is blocked. What is lacking is situation-competency. Continuous states of heightened self-consciousness (the inclination to brood over things) can contribute to action inefficacy (adequate environment-conception, negative self-concept). | |

| [3] Both the person's environmental-conception and global self-concept

are markedly negative. Objectively-present capabilities are not

actualized and a high degree of self-consciousness renders action

ineffective. (See Beck, 1967; Filipp, 1989, 1993.) |

Behavioral dis-regulation can never be described or explained solely in terms of self-concept abnormalities. To do so would be to over-generalize the relevance of information relating to self-concept. (Petermann, 1984)

The origin and modification of self-concepts can be accounted for in terms of the data- and conceptually-based assimilation of self-referencing information. (Petermann, 1984)

Seikowski (1983) cites Filipp's account of the following principal possibilities for generating self-referencing information:

| Direct Assignment of Labels: Via direct contact with other persons within a social context, a person is ascribed by them certain capabilities and qualities (e.g., "you are sick, perverted" vs. "you are healthy, normal"). | |

| Indirect Assignment of Labels: Self-referencing information is supplied by "third persons" (e.g., the media) or is even inferred from the behavior of other people. | |

| Comparative Self-Application of Labels: Insights into one's own qualities are obtained via active comparison with other persons (e.g., "I am different so far as my sexuality is concerned" vs. "I'm exactly like you"). | |

| Reflective Self-Application of Labels: Inferences regarding one's own self are drawn from the personal observation of one's own behavior (e.g., from frustrating sexual experiences with adults to an emotional/erotic/sexual interest in boys or girls). [36] | |

| Ideational Self-Application of Labels: Through the "visualization of past experiences in the sense of an "inner repetition," outcomes can be newly assimilated and existing experiences can be changed (e.g., very pleasant socialization experiences vs. traumatizing ones). |

Direct, indirect, and comparative (self-) assignment of labels represent the foundation for the construction of the ego-environment system. The ego-environment system describes self-awareness as having come into existence via interaction with the environment. Reflective and ideational self-applications of labels are the basis for the development of the ego-self system.

The two systems jointly constitute the self-concept (self-awareness). They are dependent upon one another and, at the same time, autonomous.

(Tschesnokowa, cited in Seikowski, 1983, pg. 13; see also Schröder, 1991)

In the hierarchical regulation of behavior the ego-self system, as a necessary yet not sufficient regulatory authority, occupies the highest rung. (Seikowski, 1983)

According to Petermann (1984), self-concepts are cumulatively expanded and perfected so long as self-referencing information is assimilable into the existing self-schema. On the other hand, when there is a need to adapt to self-concept-discrepant information, changes to the self-concept are required (accommodation).

The impact of ascriptions by strangers on one's self-assessment can, under isolating life-conditions and heightened self-consciousness, gain in importance and (dis-)regulatory influence. Moreover, the quantitative predominance of a single source of data, along with a limited availability of alternative sources of information, can lead to structural abnormalities in the self-concepts of members of marginal groups, along the lines of labeling theory. (Petermann, 1984)

There is a high probability that the dehumanizing and distorted image of pedophiles that is conveyed by the media will negatively affect the self-concepts of members of this marginal group. (Griesemer, 2003)