6. Presentation of Results6.1 Evaluating the Accuracy of Data Provided by Research Participants 6.1 Evaluating the Accuracy of Data Provided by Research ParticipantsWe are proceeding based on the assumption that, overall, the research participants have responded to the questions put to then frankly and honestly. This is based,

6.2 Presentation of Results Concerning First Question Posed6.2.1 Participants' Self-Image and Sexual Identity

Figure 15

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 85.9% "often" or "always" experienced their sexuality as being healthy; | |

| 14.1% of respondents "sometimes" or "rarely" experienced their sexuality as healthy. |

Of the participants,

| 84.1 % (N=69) "never" or "rarely" regarded their sexuality as an illness; | |

| 15.9% "sometimes" or "often" experienced it as such. |

Of the respondents,

| 88.9% were able to accept their sexuality; | |

| 11.1% of

participants had difficulty with this. | |

| An additional 11.1% were uncertain about their sexual orientation, which led to anxiety and problems. | |

| With 88.9% of respondents this was not the case. |

Some participants provided side-comments on certain items. Certain respondents reformulated the item-statement regarding unsureness about one's own sexual orientation: They were all too cognizant not only of their sexual orientation but also of the social problems associated with this phenomenon, which causes a great deal of anxiety and difficulty.

The age-range of interest

| to homosexually pedophilic men in this sample lay approximately between the ages of 10 and 13; | |

| for heterosexually pedophilic men it was clearly lower: between 7½ and 9 years of age. |

The average age of

| the desired boy was found to be 11.5 years; | |

| the desired girl, 8.4 years. |

At 7½ up to 14½, the predominantly erotically/sexually-interesting child age-span for bisexually pedophilic participants encompassed that of the homosexually and heterosexually pedophilic participants combined. At the same time, bisexually pedophilic men's overall age-range dipped slightly below that of homosexual and heterosexual pedophilic men. Table 8 provides an overview.

Sexual orientation |

Age-range of interest |

Average child-age |

Overall age-range |

Homosexual pedophile |

9,8 - 13,2 | 11,5 | 6 - 14 |

Heterosexual pedophile |

7,6 - 9,2 | 8,4 | 6 - 12 |

Bisexual pedophile |

7,6 - 14,6 | 11,1 | 5 - 14 |

| Sixty-two participants made statements regarding the nature of beloved boys and girls. | |

| Ten participants left this question unanswered. |

A total of 311 qualities regarding the nature of the child were mentioned.

The research participants described the nature of boys and girls whom they have actually loved as, above all,

| "curious," | |

| "self-confident," and | |

| "self-assured." |

The child would be

| "not too neat," ("verschmust“), | |

| "snug" (kuschelig")," usually | |

| "cheerful," | |

| "intelligent," and | |

| "kind." |

He or she would be

| "open-minded," and "adventurous," | |

| "open," "spontaneous," and "exuberant," sometimes | |

| "wild" and hopefully even | |

| “a little fresh." |

Even qualities such as

| "pensive," | |

| "quiet," and | |

| "tender" |

were mentioned several times.

At the same time, respondents also named some "negative qualities" such as

| "egotistical," | |

| "lazy at school," | |

| "untidy,” | |

| "moody," | |

| "stubborn," and | |

| "not very reliable." |

With one exception, the attributes used by heterosexually pedophilic participants to describe beloved girls were not demonstrably different from those employed by homosexually pedophilic participants to describe desired boys.

As was the beloved boy, so too was the beloved girl often described as

| “curious," | |

| "self-confident," and | |

| "self-assured," in part as | |

| "exuberant," and sometimes as | |

| "quiet" and | |

| "tender." |

In contrast to

the desired boy, however,

[page 63] the desired girl was not described as

"fresh" or even expressly as hopefully “a little fresh"

by the heterosexually pedophilic participants.

| Sixty-three participants provided statements regarding their attraction to children's bodies and outward appearance generally. | |

| Nine participants left this question unanswered. |

A total of 213 attractive aspects were named. For the overall number of aspects mentioned, the average homogeneity of opinion between two independent raters amounted to 95.6%

The respondents named a large number of admired external characteristics from head to toe.

The majority of the participants stated explicitly that the boys and girls who they find attractive are

| "thin” and | |

| "slender," or at least | |

| "not fat." |

Their outward appearances and bodies are hailed as

| "good-looking," | |

| "nice," | |

| "cute," and | |

|

"well-formed." | |

| To some men, rather androgynous appearances (e.g., "delicate, tender boys" or “girls with slender hips") are appealing. | |

| Others, on the other hand, explicitly describe or prefer a typically boyish appearance. |

An important factor in assessing the child's exterior is the absence of body hair or the presence of a physically pre-pubertal appearance. The eyes, the hair, the face, and the skin were mentioned particularly frequently as attractive aspects.

| The eyes are described as "beautiful and "intensely expressive.” Light- as well as dark-colored eyes were deemed attractive by respondents. | |

| The hair would be "short," or "long," the child's countenance “open,” "cheerful,” and "friendly.” | |

| Many participants describe and like a rather narrow face; with others, preference is given to a rather round and soft face. | |

| A boy or girl with a slight tan is expressly prized by many of the men. | |

| Furthermore the softness and smoothness of the skin is also desirable. |

Some participants stressed that the child's outward appearance was more or less all the same to them, so long as an age-corresponding pre-pubertal appearance were present. To them, the boy or girl's nature was seen as far more important than the child's outward appearance.

There were even research participants who preferred specific features such as

| "freckles," | |

| "a large back-of-the-head," | |

| "erotic contrasts" (“blond hair and brown eyes"), and | |

| "braces." |

Children's affectionate, beaming, and loving smiles were also deemed attractive. Boys' and girls'

| "snub noses," | |

| "infatuating scents," | |

| "voices," | |

| "fantastic stomachs," | |

| "feet," | |

| "fingers," as well as a | |

| "nice backside" or | |

| "beautiful bottom" |

were mentioned as praiseworthy.

There were no mentions or descriptions of children's genitalia.

Homosexual, heterosexual, and bisexual pedophile participants were not demonstrably different in terms of their descriptions of boys and girls.

To the question, "What do you see as the causes of your sexual orientation?," close to a third of the participants explicitly plead ignorance:

| "I can't name any cause. I consider it part of my personality, since I've had these feelings for as long as I can remember." | |

| "None, it’s a mystery to me." | |

| "Though I've thought about it a lot, I just don't know." | |

| "I don’t see how I could find the answer to this question. Accordingly, I haven’t been preoccupied with it." | |

| "I don’t know. Whatever it is that makes people want to have sexual contact with adults, it doesn't apply to me." |

| Seventeen participants left the causality question unanswered. | |

| Eleven participants tendered a purely endogenous causal explanation, and | |

| 12, a purely exogenous one. | |

| Nine participants cited an interaction between predispositional and environmental factors as the origin of their sexual orientation. |

Table 9, with a breakdown by participants' pedophilic

orientation, provides an overview.

[64]

Cause |

Overall frequency | Homosex... ped... | Heterosex... ped... | Bisex... ped... |

Predisposition |

15.3 % | 10 | 0 | 1 |

Environment |

16.7 % | 12 | 0 | 0 |

Predisposition / Environment |

12.5 % | 8 | 1 | 0 |

Don't know |

31.9 % | 19 | 2 | 2 |

No statement |

23.6 % | 12 | 4 | 1 |

The research participants' endogenous, subjective theories relate to genetic and biochemical factors. Most responses were in broad terms, such as

| "genetics," | |

| "freak of nature," | |

| "accident," or | |

| "natural variability." | |

| One participant based his genetic, subjective theory on the fact that he had distant relatives who were pedophiles. | |

| Another participant was sure that he had a genetic predisposition because he was not aware of any environmental triggers for his pedophilic feelings. |

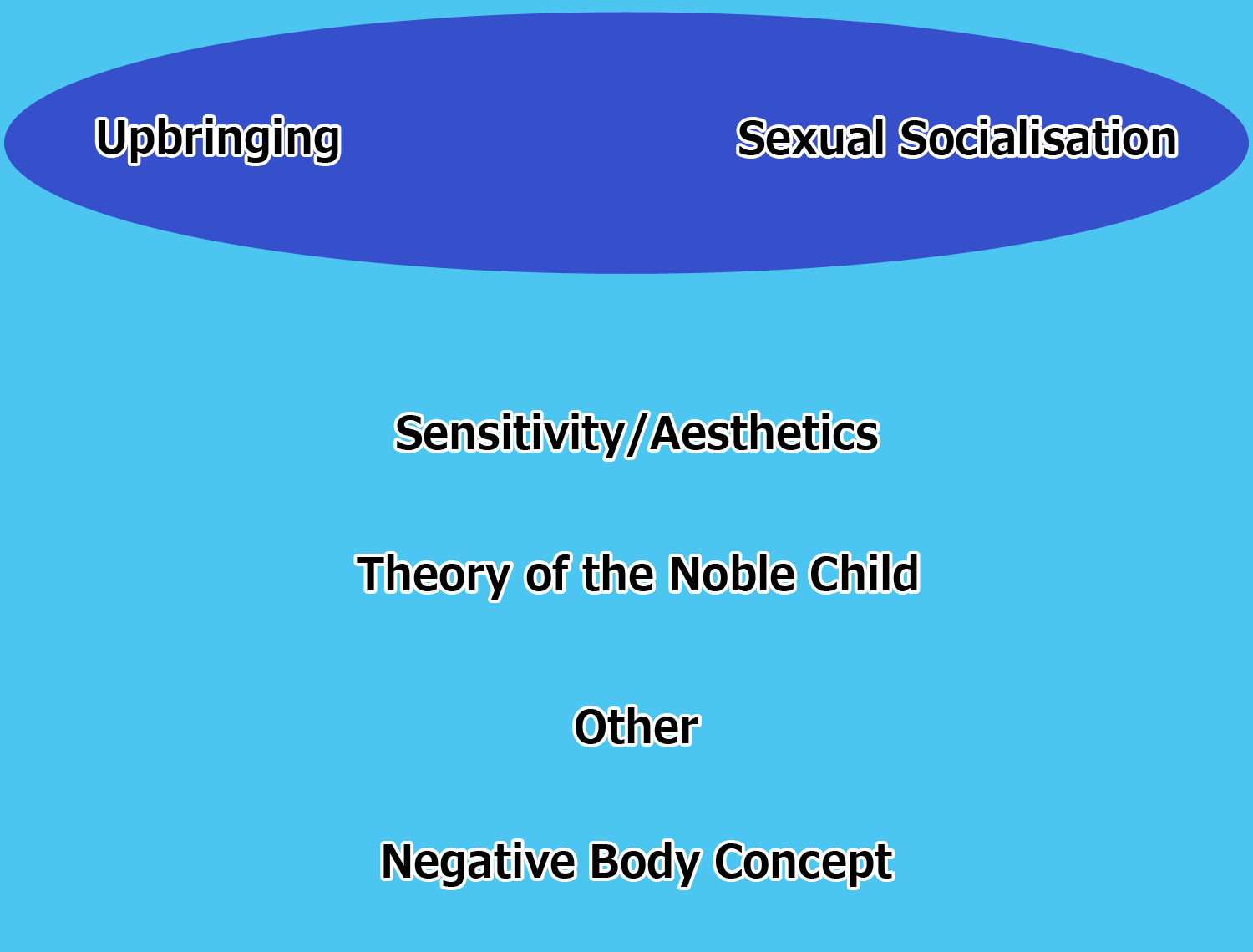

The exogenous factors presumed by the research participants can essentially be placed into the two main categories of

| “upbringing" and | |||

| "sexual

socialization," as well as the subcategory of

|

Falling into the two additional sub-categories of

| "sensitivity and esthetics" and | |

| "negative body-concept" |

are statements where the reasons for one's own sexual orientation are regarded as lying within one's character. The remaining eight remarks were put in the "other" category. The average homogeneity of opinion between two independent raters amounted to 86.6%.

In the main category of upbringing, a "lack of maternal love" was often mentioned as the cause, and the absence of male role-models was pointed to. Several times a "strict parental upbringing" along with too little "parental warmth," "tenderness," and "physicality" were mentioned in general terms, without reference to the mother or father.

Participants also cited "parental domestic violence" as well as "experiences in the home" as possible causes.

Falling into the main category of sexual socialization were most mentioning of positively-experienced sexual experiences with other children (playing doctor). There were also, however, statements from participants who regarded the lack of sexual experiences during childhood with same-age peers as itself being the substantial cause for the formation of a pedophilic orientation.

Two participants explicitly pointed to Griesemer's (2004a, 2005) neurological learning theory-based imprinting hypothesis as being applicable to them.

Positively- or

negatively-experienced “sexual contacts with adults” during

childhood were occasionally mentioned as

[p. 65]

further potential causes.

One item mentioned referred to a consensual contact with a pedophilic man, another to a contact by the biological mother that was experienced as sexual violence.

The lack of education about sex was also cited as a possible reason.

In the sub-category of sensitivity and esthetics, five participants praised the beauty and esthetics of boys or children in general, pointing to a spiritual connection between boys and men. Also falling into this category was a comment about possessing the “sensitivity” and the “courage” to perceive one’s sexuality.

Three responses constituted the theories of the precious child. These have as their subject the “innocence” and better characteristics of the child relative to adults.

Two participants saw the self-rejection of their own outward appearances as a reason for their sexual orientation.

Seven isolated statements, such as the “dissolution of one’s own vitality,” were placed into a remainder category.

In the questionnaire, about one-fifth of the participants also expressed their displeasure with the etiological paradigm itself: It would not be appropriate to pursue the question of causality because, analogous to homosexuality it is, of course, ultimately unanswerable. Though there are numerous medical and psychological theories about it, none have gained wide acceptance. Lastly, science and society as well should accept the pedophilic orientation:

“This is how it is and it cannot be changed”

(citing one research participant).

The following presents an overview of participants’ sexual socialization experiences with similar-age peers in childhood, the teenage years, and adulthood based on the criteria

| “presence,” | |

| “partner selection,” and | |

| “evaluation.” |

As children, teenagers, or adults, the majority of the participants did have sexual experiences with similar-age peers. Figure 17 provides an overview.

| Fifty-one participants (70.8%) reported sexual experiences with peers ("playing doctor") during childhood. | |

| For 20 participants (27.8%), these sexual socialization experiences were not present. | |

| One

participant (1.4%) did not provide a statement regarding this issue. | |

| With 42 participants (58.3%), there had been sexual experiences with similar-age peers in the teenage years. | |

| Thirty participants (41.7%) had not had these sexual contacts. | |

| Fifty-eight participants (80.6%) reported sexual experiences in adulthood with other adults. | |

| Fourteen participants (19.4%) had not verified their pedophilic orientations via experiences with adult sexual partners. |

[p. 66]

Whereas sexual contacts primarily with male peers were reported in

childhood and the teenage years, in adulthood there was an increase in

sexual experiences involving both men and women. Figure 18 provides an

overview.

| For 31 of 51 participants (60.8%), sexual experiences in childhood involved boys exclusively; | |

| for two participants (3.9%), exclusively girls. | |

| Eighteen participants (35.3%) mentioned having had erotic/sexual contacts with both boys and girls. |

In the teenage years,

| 31 participants (73.8%) had sexual experiences exclusively with male youth, | |

| four (9.5%) with female youth, and | |

| seven (16.7%) with teenagers of both genders. |

In adulthood,

| 18 of 58 participants (31.0%) [p. 67] had sexual contacts exclusively with men, | |

| 14 (24.1%) exclusively with women. | |

| Twenty-six

participants (44.8%) reported sexual contacts with both men and women. |

The overwhelming majority of participants reported pleasant childhood sexual socialization experiences with same-age peers. However, the number of participants with pleasant sexual experiences involving same-age peers then continuously diminished through the teenage years and into adulthood. Figures 19 [page 67] and 20 [page 68] provide overviews.

| Forty-four of 49 participants (89.8%) with sexual experiences involving other boys evaluated these experiences as pleasant, and | |

| five (10.2%) as neutral or unpleasant. |

Sexual experiences with other male teenagers were perceived

| by 78.9% of affected participants as pleasant, and | |

| by 21.1% as neutral or unpleasant. |

In adulthood,

| 54.4% of participants with sexual contacts involving other men evaluated these experiences as pleasant, and | |

| 45.5% as neutral or unpleasant. |

As to sexual experiences involving peer girls,

| 16 of 20 affected participants (80.0%) evaluated these as pleasant, | |

| four (20.0%) as unpleasant. |

Sexual contacts involving female teenagers were evaluated

| by 63.6% of affected participants as pleasant, | |

| by 36.4% as neutral or unpleasant. |

In adulthood,

| 37.5% of participants with sexual contacts involving women had experienced these as pleasant, and | |

| 62.5% as neutral or unpleasant. |

Indeed, in personal conversations, participants again and again spoke of frustrating sexual experiences with adults. One participant evaluated his sexual experience with a woman as follows:

“It was like rabbits, who run around copulating with each other – simply ridiculous.”

[p. 68]

To the question as to whether sexuality was dealt with openly in the home,

| the major portion of participants (68.1%) said no. | |

| The home was described as an open one by 29.2% of participants. | |

| Two participants (2.7%) did not respond to this question. |

At the same time, a small group of 10 pedophilic men (13.9%) with either no or very few sexual socialization experiences was able to be identified:

| Six participants (8.3%) evinced no sexual experiences with similar-age peers in childhood, the teenage years, or adulthood, and with | |

| four participants

(5.6%), sexual experiences were limited to doctor games in childhood. |

| Seventeen participants (23.6%) made the statement that they had been approached sexually by women or men during their own childhoods. | |

| For 55 participants (76.4%) there were no pedosexual contacts, as children, with adults. |

The sexual contacts with adults were mostly evaluated

| as pleasant (52.9%), and sometimes | |

| as neutral (23.5%) or | |

| unpleasant (23.5%). |

Figures 21 and 22 provide overviews.

[p 69]

Of the 17 participants with pedosexual contacts during their own childhoods, four made the statement that they had been in pedosexual relationships with women or men that lasted for over a year and, without exception, evaluate these experiences retrospectively as "pleasant." In cases of pedosexual relationships of a year or more in duration, the child's average age is taken as the point of departure.

Age as child / teen |

Number of participants |

Evaluation of sexual contacts |

||

Pleasant |

Neutral |

Unpleasant |

||

| 6 | 1 | 1 x woman | ||

| 9 | 1 | 1 x man | ||

| 10 | 5 | 2 x woman 1 x man |

1 x man | 1 x woman & man |

| 12 | 4 | 1 x woman 1 x man |

1 x man | 1 x woman |

| 13 | 2 | 1 x man | 1 x man | |

| 14 | 3 | 1 x man | 1 x man | 1 x man |

| 16 | 1 | 1 x man | ||

There is no significant association between the expression of the characteristics “pedosexual contact as an adult" and "pedosexual contact as a child with adults." Table 11 provides an overview.

Sexual contact as child with adults |

Pedosexual experience as adult |

||

Yes |

No |

Overall |

|

Yes |

14 | 3 | 17 |

No |

35 | 20 | 55 |

Total |

49 | 23 | 72 |

| About two-thirds of participants evaluated the statement, "pedophiles cannot lead a well-balanced life without living out their sexuality," as being applicable to themselves (65.3%). | |

| About one-third evaluated this statement as being only partially or not at all applicable to them personally (34.8%). |

Of participants,

| 86.1% would like to have a pedosexual relationship with a boy or girl; | |

| 11.1% of respondents ruled this out for themselves. | |

| Two participants (2.8%) did not provide a statement. |

Of participants, 94.4% stressed that the gender of the child was critical -- i.e., that it would matter whether we were talking about a relationship with a boy, or a girl.

At the time the data was collected,

| eight participants (11.1%) were involved in relationships with boys or girls which included pedosexual contacts. | |

| Forty-three respondents (59.7%) made the statement that, whereas they had in fact had pedosexual contacts in the past, there were no pedosexual contacts presently taking place. | |

| Twenty-one participants (29.2%) had never had any sexual contact with boys or girls. |

Figure 23 provides an overview of the characteristic "presence of pedosexual contacts." [70]

The connection between the characteristics "pedosexual contact" and "age group" is depicted in Figure 24 (exact Fisher Test p=0.027).

A higher proportion of participants without pedosexual contacts was to be found above all in Age Group 1, and much more rarely in Age Groups 3 and 4. More than half of the participants from Age Group 1 had never been involved in any pedosexual contacts. On the other hand, only one participant from Age Groups 3 and 4 evinced a pedosexually abstinent biography. Of the participants from Age Group 2, 29.2% had no pedosexual experience.

The characteristics "pedosexual experience in the past" is more pronounced among middle-to-older-age participants.

In Age Group 2 (58.3%) and especially in Age Group 1 (36.4%), the relative percentages of respondents with pedosexual experiences in the past were clearly lower than those in Age Groups 3 and 4. Participants currently in pedosexual relationships were distributed relatively homogeneously, and in smaller numbers, across all four age-groups.

[71] When asked about sexual practices, 69 participants (95.8%) made the statement that they either rejected 'heavy' practices such as anal or vaginal intercourse entirely or in part, or found them sexually unappealing or only of limited interest.

Sexual practices essentially consisted of caressing, stroking, and licking. In personal conversations

(as well as in answers to the open-ended solicitation of a self-description of one's own nature from the child’s point of view),

those questioned expressed a great need to be physically close to children.

They often characterized themselves as a "friend,” a “role model," and a "supporter," and sometimes as a "protector." Friendship and an emotional bond with the loved boy or loved girl would be central.

They hold themselves out as being "different from most other adults"; that is, seriously interested in their small counterparts, and always willing to listen to their young friends' problems. Sexual contacts and, sexual play (erotic embraces, playful caressing and petting) are considered important components of pedosexual relationships.

Three participants (4.2%) in this sample found 'heavier' practices to be appealing sexually.

Sixty-eight participants (94.4%) concurred with the statement that their own well-being would largely depend on the willing participation of the child. For four participants (5.6%), the child's voluntary participation was of little importance to their own well-being.

Almost without exception, participants (97.3%) regarded pedophilia as a sexual form in its own right, clearly distinguishable from sexual abuse in terms of the pedosexual contacts in which boys or girls are involved. Two participants (2.7%) did not agree with this point of view.

One participant described his sexuality in a letter that was enclosed with the questionnaire. Although this description may well reflect a not inconsiderable portion of pedosexual reality, it cannot be regarded as generally applicable to the sexuality of primarily pedophilic men as a whole.

“The only sexual relationship I've ever had was with a young person many years ago; but to use the term 'relationship' is perhaps overstating things. There were occasional sexual contacts, with this young person I was friends with, over a period of time of about 18 months. At that time, I let myself get involved with him because he was already somewhat older, outgoing and, last but not least, because I could trust him. Although he was then certainly at an age which no longer corresponded to my ideal type, I found him to be indescribably beautiful.

Perhaps also of interest is the fact that he very much wanted to try it out, whereupon, I was glad to do it, provided that the sexual practices were not of a kind as to simply serve my own sexual needs. This was due, for one, to the fact that he had never expressed the desire, and for another, that this would not have been important at all to me either. I had a much greater interest in satisfying and

[72]

pampering him. I could also satisfy myself personally alone later on, remembering it at the same time.Only once did he (somewhat astonished) ask me whether I really had no interest in him doing it to me with his hand. At which point I said that I would be happy for him to do this, if he really wanted to. But I also told him that to me this was not so important, and that he simply should not think that he's obliged to do it so to speak as compensation (for my services), but only if he would truly like to.

In a subsequent conversation, my assumption was proven correct. He indeed would have done it for my sake, but he didn't really want it out of his own interests, and therefore the subject never came up again.

Today, of course, this young person has long since grown up; but I still see him often, and even today he still numbers among my closest friends. No one ever found out about the sexual contacts.

Perhaps also of interest is the fact that (contrary to current prejudice) at the time, it was not I who said to him but rather he who said to me: ‘But please keep this between us,’ whereupon I said only: 'Of course I trust it will'.”

| Sixty-two respondents (86.1%), made the statement that they had privately made use of images of children, which can encompass both legal and illegal spheres. | |

| For 10 participants (13.9%) this was not the case. |

In relation to those in Age Groups 1, 2, and 3, participants in Age Group 4 used images of children less frequently. Figure 26 provides an overview.

No significant association exists between the expressions of the characteristics "pedosexual relationship" (never, previously, currently), and "use of child erotica/pornography." Table 12 provides an overview. [73]

Use of pornography |

Pedosexual relationship |

|||

Never |

Previously |

Currently |

Overall |

|

Yes |

17 | 38 | 7 | 62 |

No |

4 | 5 | 1 | 10 |

Total |

21 | 43 | 8 | 72 |

(Considering the Self-Concept Characteristics, Feelings of Being Under Stress, and Sense of Well-Being Among Pedophilic Men in General).

In the following, research participants are compared with a heterosexual control group (N=33; 18 women and 15 men) and normative values for the general population with regard to self-image characteristics, feelings of being under stress, and sense of well-being. In the sexual self-concept comparison, research participants exhibited significant differences from the heterosexual control group on 16 of the 20 MSSCQ sub-scales. Figures 27a and 27b provide overviews.

For pedophilic men, there were significantly higher values on the sub-scales of

|

"sexual anxiety" (p<.001), | |

|

"sexual consciousness" (p<.001), | |

|

"external sexual control" (fate) (p< .001), | |

|

"sexual fixation" (p< .001), | |

|

"sexual self-monitoring" (p<.001), | |

|

“external sexual control (others)" (p=.025), | |

|

"sexual fears" (p <.001), and | |

|

"sexual depression" (p<. 001). |

[74]

Significantly lower mean values were found among the research participants on the sub-scales of

| "sexual self-efficacy" (p<.001), | |

| "sexual clarity" (p<.001), | |

| "sexual optimism" (p<.001), | |

| "blaming oneself for one's sexual problems" (p=.002), | |

| "sexual motivation" (p=.004), | |

| "personal responsibility for solving sexual problems" (p=.003), | |

| "sexual self-satisfaction" (p<.001), and | |

| "internal sexual control" (p=.009). |

Although the sub-scales of

|

"risky sex," | |

|

"sexual self-respect," | |

|

"sexual self-schema," and | |

|

"consciousness of sexual problems" |

were less strongly pronounced than those of the heterosexual control group, they were not excessively so.

In the Self-Image of Functional Social Potency, pedophilic men, in comparison with the heterosexual control group, produced significantly lower values on the "communicability" sub-scale (p<.001).

Although the sub-scales of

|

"consciousness of one's control over the environment" and | |

|

"consciousness of self-control" |

were slightly less pronounced than those of the heterosexual control group, these differences were not statistically significant.

There were nearly identical values on the "de-centering” sub-scale. Pedophilic men and the heterosexual control group were not statistically distinguishable from one another on the "de-centering" sub-scale. Figure 28 provides an overview.

[75] With regard to the characteristics of self-attention, the pedophilic men showed no differences relative to a normative sample of "healthy" persons (N=771). Stanine values were applied (stanine norm average range: four through six). For the research participants the value for

|

"private self-attention" was 5.3 with a standard deviation of 1.7, and the value for | |

|

"public self-attention" was 4.8 with a standard deviation of 2.0. |

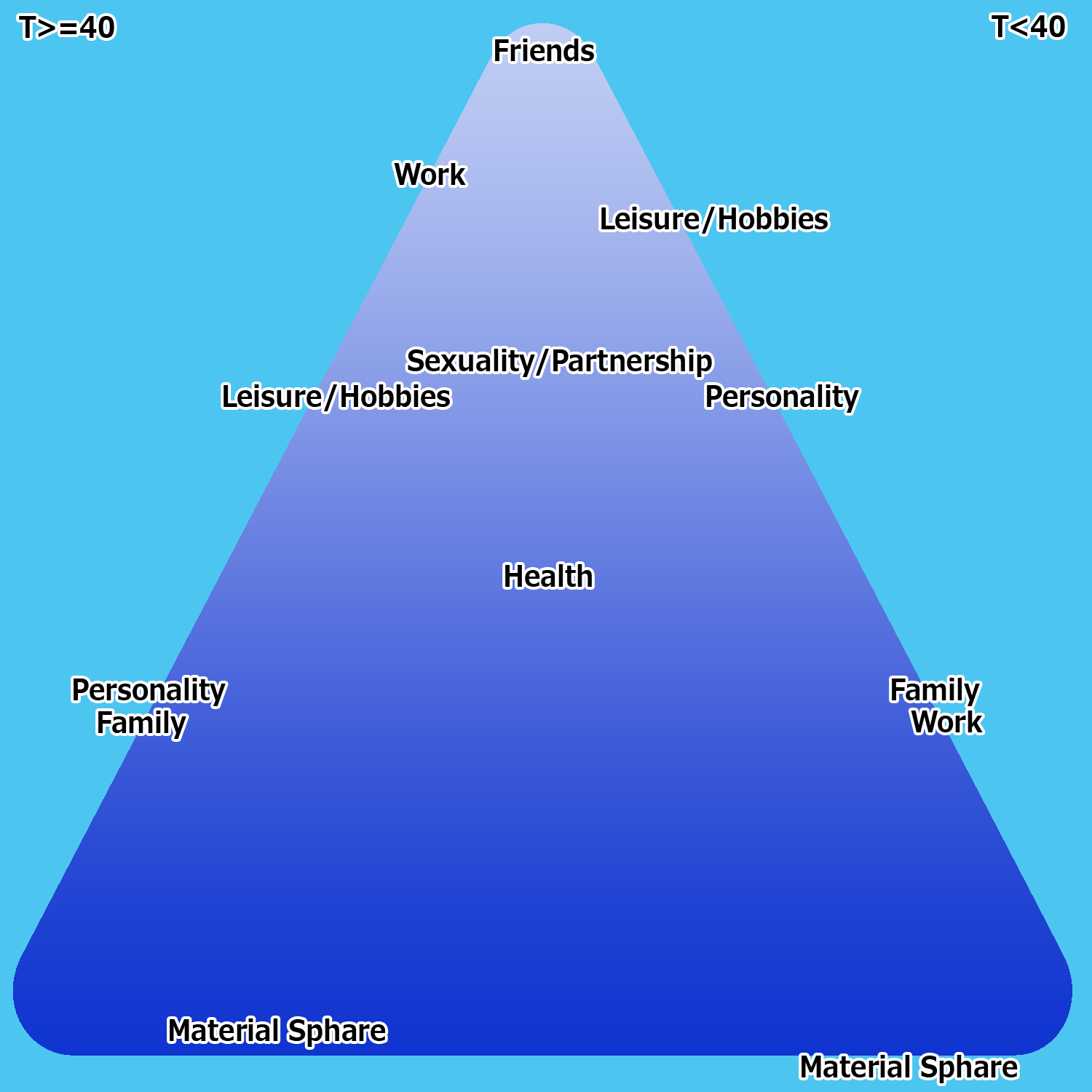

Relative to the TPF's (N=436) normative male sample, the pedophilic men manifested an in part below-average sense of well-being. Figure 29 provides an overview of the characteristics assessed by the TPF sub-scales.

Respondents produced values less than those of the norm in the TPF sub-scales of

|

"mental health" (T=39.0; standard deviation 13.8) and | |

|

"sense of fulfillment" (T=39.2; standard deviation 15.2). |

In the remainder of the TPF sub-scales, characteristics had, without exception, below-average scores (T>40 through T<50). The standard deviation of these scales lay between 8.6 and 14.1. The expressed characteristic distribution for the central sub-scale of "mental health" is depicted in Figure 30.

On the "mental health" sub-scale, 51.4% of participants evinced below-average scores (T<40). Average scores were attained by 40.3% of respondents, and above-average scores (T>60) by 8.3%.

[76] Relative to the normative sample from the SCL-90-R (N=501), the pedophilic men had, in part, above-average feelings of being under stress. Figure 31 provides an overview of the characteristics assessed by the SCL-90-R sub-scales.

Among the research participants, above-average values were present on the sub-scales of

|

"depressiveness" (T=63.2; standard deviation 12.4), | |

|

"global severity index" (T=61.2; standard deviation 12.6), and | |

|

"positive symptom distress index" (T=61.7; standard deviation 10.5). |

In the remainder of the sub-scales, the characteristics had -- without exception -- above-average ranges (T>50 through T<60). The standard deviations for these sub-scales fluctuated between 11.6 and 13.4.

Via the items from the SCL-90-R, it is possible to roughly estimate participants' risk of suicide

(Item 15: "thoughts about taking one's life"; Item 59: "thoughts about death and dying").

At the time of the data collection,

|

18 respondents (25.0%) were at risk of suicide, with | |

|

54 participants (75.0%) not at risk. |

Figure 32 provides all overview of the characteristics "age group" and "suicide risk." Relative to Age Groups 3 and 4, participants from Age Group 1, and particularly from Age Group 2, were at higher risk of suicide. However, a strong association between the characteristics of "age group" and "suicide risk" was not discernible.

[77]

(Considering the Self-Concept Characteristics, Feelings of Being Under Stress, and Sense of Well-Being Among Pedophilic Men with "Positive" and "Negative" Sexual Self-Concepts)

In the following, based on a two-cluster solution, research participants are compared with a heterosexual control group and normative values in terms of self-concept characteristics, feelings of being under stress, and sense of well-being.

The initial partition generated via the MSSCQ sub-scales (Ward method) was amended through a subsequent central cluster analysis (K means method). Various potential solutions were verified and evaluated as to their statistical significance with regard to demographic as well as sexual characteristics by means of chi-square tests.

The selected two-cluster solution consists of

|

one group of pedophilic men with a pronounced "positive" sexual self-concept (Cluster 1; N=34) and | |

|

a group of pedophilic men with markedly "negative" sexual self-concept (Cluster 2; N=38). |

The groups differ from one another predominantly in terms of the distribution of demographic characteristics as well as general and -- not surprisingly -- sexual influence factors.

Existing differences between participants from Cluster 1 versus Cluster 2 could be ascertained only with regard to the following characteristics:

|

"suspected alcohol abuse" (0% in Cluster 1 vs. 15.8% in Cluster 2; p=.026), | |

|

"suicide risk" (11.8% in Cluster 1 vs. 36.8% in Cluster 2; p=.016), | |

|

"sexual orientation towards adults not verified" (8.8% in Cluster 1 vs. 28.9% in Cluster 2; p=.039), and | |

|

"sexual self-acceptance" (item: "I have problems accepting my sexuality"; 0% in Cluster 1 vs. 21.1% in Cluster 2; p=.006). |

Comparing the two-cluster solution with the heterosexual control

group showed that, on average, control group participants had a clearly

more "positive" sexual self-concept on all of the scales of

the cluster solution than participants from Cluster 2 (p<.001

throughout). Even among the pedophilic men from Cluster 1 there existed

significantly "worse" values compared with the heterosexual

control group, with the exception of the "sexual self-respect"

and "external sexual control (others)" sub-scales. Figure 33

provides an overview.

[78]

Blue = Cluster 1 (Positive sexual self-concept)

Pink = Cluster 2 (Negative sexual self-concept)

Brown line & green dots= (Heterosexual) Control group

A comparison of the two-cluster solution with the heterosexual control group with regard to the self-image of functional social potency produced the following picture: There are no significant differences between Cluster 1 and the heterosexual control group on any of the four SSF sub-scales.

Cluster 1 and Cluster 2, on the other hand, had statistically significant differences on all four sub-scales

|

("communicability” p<.001; | |

|

“de-centering” p=.002; | |

|

“consciousness of one's control over the environment" (p=.006; | |

|

"consciousness of self-control" p=.020). |

Significant differences between the heterosexual control group and Cluster 2 existed on the sub-scales of

|

"communicability" (p<.001) and | |

|

"consciousness of one's control over the environment" (p=.012), but not on the sub-scales of | |

|

"de-centering" and "consciousness of

self-control." |

[79] When the two-cluster solution with regard to the characteristic of self-attention was compared with the normative values of "healthy persons," it was shown that Cluster 1 had a below-average range of scores on the "public self-attention” sub-scale (stanine=4.1; standard deviation 1.4).

And there is also a significant difference between Cluster 1 and Cluster 2 on the sub-scale of "public self-attention" (p<.001). Cluster 2 has a mean "public self-attention" score of 5.7 and a standard deviation of 1.6. On the sub-scale of "private self-attention," there are no significant differences between Cluster 1 (stanine= 4.9; standard deviation 1.8) and Cluster 2 (stanine=5.7; standard deviation 1.6) (p=.055). Figure 35 provides an overview.

Comparing Cluster 1 and Cluster 2 with normative samples on the TPF and SCL-90-R produces the following picture:

|

On average, pedophilic men with a "positive" sexual self-concept score in the mean range on the TPF and SCL-90-R sub-scales. | |

|

Pedophilic men with a "negative" sexual self-concept evince health-related damage on a large number of the TPF and SCL-90-R sub-scales. Figures 36 and 37 provide overviews. |

[80]

Also in relation to feelings of being under stress, the Short Stress-Test showed statistically significant mean differences on the sub-scales of

|

"loss of control" (p<.001), | |

|

"loss of meaning" (p=.003), | |

|

"anger" (p<.001), | |

|

"sleep disturbances" (p=.002), | |

|

"inability to relax" (p<.001), and | |

|

"current source of stress" (p<.001); | |

|

"absence of social control." |

(Differential Assessment of Pedophilic Men)

The research participants were subdivided into groups based on selected influence factors and compared with regard to

|

self-concept characteristics, | |

|

feelings of being under stress, and | |

|

sense of well-being. |

In the self-concept spheres of sexuality, functional social potency and self-attention, rank-variance analyses and U-tests were unable to demonstrate any significant mean differences between homosexual, heterosexual, and bisexual pedophile participants.

A rank-order analytical comparison of the

three sub-groups did reveal a significant mean difference on the

"behavioral control" TPF sub-scale (p=.029). On average,

homosexually pedophilic men had T-values comparable to those of

heterosexually and bisexually pedophilic men. Figure 38 provides an

overview of the characteristics assessed by the TPF sub-scales.

[81]

A direct, individual comparison (U-test) of homosexually and heterosexually pedophilic with bisexually pedophilic men showed no significant differences on any of the TPF sub-scales.

There was a significant difference between homosexually and heterosexually pedophilic men on the sub-scale of "expansiveness" (p=.027). On average, heterosexually pedophilic participants represented themselves as more capable of carrying things through, more dominant, and more self-confident than the homosexually pedophilic men.

On the sub-scales of the SCL-90-R, there were no statistically significant mean differences among the sub-groups (rank-variance analysis and U-test). Among all three sub-groups, there were heightened T-values (T>60) on the "depressiveness" and "global severity index" sub-scales.

On average, participants from the four age-groups differed in terms of sexual self-concept on the sub-scales of "sexual anxiety" (p=0.011) and "external sexual control (others)" (p=.026). As Figure 39 makes apparent, a particularly clear difference exists between Age Group 4 and Age Group 2 on the "sexual anxiety" sub-scale (p=.004).

As to the self-image of functional social potency, there were no significant mean differences among age-groups. With the exception of "de-centering," Age Group 1 had higher average rank-positions than Age Groups 2 and 3 on all sub-scales.

Significant mean differences between age-groups existed with regard to the "public self-attention" sub-scale (p=.005), but not on the "private self-attention" sub-scale (rank-variance analysis).

Through direct individual comparison (U-test), it was able to be shown that Age Group 4 evinced statistically lower scores (stanine=3.3; standard deviation 1.1) than all other age-groups (average values) with regard to "public self-attention." Age Groups 1, 2, and 3 did not differ from one another in individual comparisons on the "public self-attention" sub-scale.

In the TPF, there were significant differences among the age-groups, in rank-variance analytic comparison, on the sub-scales of "carefree-ness" (p:.043) and "autonomy" (p=.031). The differences between Age Groups 4 and 2 were great. On most of the TPF sub-scales, Age Group 4 had Higher scores than the other age groups. Figure 40 provides an overview.

* 0-60 = T value

The older participants manifested average T-values across all sub-scales. But they differed significantly from the participants from Age Group 2 on the sub-scales of

|

"sense of fulfillment" (p=.016), | |

|

"carefree-ness" (p=.008), | |

|

"expansiveness" (p=.049), and | |

|

"autonomy" (p=.005). |

Age Group 4 evinced a greater "ability to love" (p=.036) and greater "expansiveness" (p=.030) than Age Group 3. Age Group 4 had higher values on the sub-scale of "autonomy" than Age Group 1 (p=.019). There were higher values among Age Group 1 on the "ability to love" sub-scale (p=.038) compared with Age Group 3. There were no significant mean differences in the TPF between Age Groups 1 and 2 or between Age Groups 2 and 3.

Rank-variance analysis of the SCL-90-R sub-scales demonstrated no significant differences among Age groups. A U-test, however, showed that there were significantly higher "depressiveness" scores in Age Group 2 (T=67.9; standard deviation 12.4) than in Age Group 4 (T=59.2; standard deviation 11.3) (p=.039).

Figure 41 provides an overview.

[83]

* 0-80 = T value

Compared with the employed, students, and retirees, among the unemployed the self-image of functional social potency is characterized primarily by a weaker expression of the characteristic. "consciousness of one's control over the environment" (p=.017).

As shown by the "average T-values across all of the TPF and SCL-90-R sub-scales, the unemployed also exhibited clearly diminished scores in the health-related sphere on the "sense of fulfillment" sub-scale (T=31.6; standard deviation 14.3), 'especially compared with retirees (p=.014).

Among the employed and student groups, there were below-average T-values of about 39 on the sub-scales of "mental health" and "sense of fulfillment." The employed and students did not differ from one another in terms of their feelings of being under stress and sense of well-being; with the exception of the "sense of fulfillment" sub-scale, they also did not differ from the unemployed group (employed only p=.041).

Furthermore, retirees had significantly lower scores than the unemployed (p=.008), students (p=.012), and the employed (p=.027) on the "duress" sub-scale (T=47.8; standard deviation 8.6).

As to sexual self-concept, participants with previous criminal convictions exhibited higher scores than those without previous convictions on the sub-scales of "sexual self-monitoring" (p=.039) and "external control (others)" (p=.036).

No significant mean differences were found on the self-image

of functional social potency scale and the self-attention scales. There

were no significant mean differences on the TPF either. Relative to

those without previous convictions (T=57.8; standard deviation 13.0),

participants with previous criminal convictions had a significantly

higher score (p=.014) on the SCL-90-R "paranoia" sub-scale

(T=64.9 standard deviation 8.2).

[84]

Participants with no therapy experience (N=34) were compared with participants who had been in therapy previously (N=19) as well as those who were currently in therapy (N=19).

With regard to sexual self-concept, a rank-variance analytical comparison showed a significant mean difference on the "sexual optimism" sub-scale (p=.022). Therapeutically inexperienced participants were more sexually optimistic than pedophilic men who were currently in therapy (p=.005). There were no significant differences among the three sub-groups on any of the other MSSCQ sub-scales. Although not significant, there was a trend to the direction of therapeutically inexperienced participants evincing a more "positive" sexual self-concept than participants who were in therapy currently. Figure 42 graphically illustrates this trend.

* 0 - 2,5 = Mean MSSCQ

With the exception of the "consciousness of self-contro1" sub-scale, there were no significant differences among the three sub-groups with regard to the self-image of functional social potency. Therapeutically inexperienced participants had a greater consciousness of self-control than participants who had previously been in therapy (p=.035). Although those currently in therapy had even higher scores, the difference was not great.

There were significant mean differences (rank-variance analysis) on the TPF sub-scales of "mental health" (p=.014) and "sense of meaning" (p=.031). Psychotherapeutically inexperienced participants attained higher health scores than psychotherapeutically experienced participants.

Participants

who had previously sought out -- or had been

obliged to seek out -- psychotherapy showed lower scores than

psychotherapeutically inexperienced participants on the "mental

health" sub-scale (p=.035). Respondents currently in psychotherapy

had lower scores on the sub-scales of "mental health" (p=.008)

and "sense of meaning" (p=.009) compared with

psychotherapeutically experienced participants. There were no

significant differences between participants who had previously been in

therapy versus those currently in therapy in terms of health-related

characteristics.

[85]

* 10-80 = T value

No significant mean differences among the sub-groups were found on the SCL-90-R sub-scales (rank-variance analysis). The U-test, however, did reveal differences on the "duress" sub-scale. Participants currently in therapy portrayed themselves as being under significantly more duress (T=62.4; standard deviation 12.8) than both participants with no psychotherapeutic experience (T=56.2; p=.039) as well as those who had previously been in psychotherapy (T=55.5; p=.037).

Using six items designed to roughly capture the construct of "social support", research participants were classified based on the extent to which it was present

|

(0-2 points: "not present"; | |

|

2-4 points: "partially present"; | |

|

4-6

points: sufficiently present"). |

Social support |

Sufficiently present |

Partially present |

Not present |

| Number of respondents | 39 | 27 | 6 |

| Percent | 54.2 % | 37.5 % | 8.3 % |

With the self-image of functional social potency, there was a significant difference among the three sub-groups on the "consciousness of self-control" sub-scale (p=.016). Participants with "sufficiently present" social support evinced a greater "consciousness of self-control" and greater "communicability" (p.044) compared to participants with "partially present" social support.

[86] Participants with "present" social support attained almost thoroughly average T-values on the TPF and SCL-90-R sub-scales. In a rank-variance analytical comparison, participants with "not present" or "partially present" social support on the sub-scales of

|

"mental health" (p=.046), | |

|

"sense of meaning" (p=.030), | |

|

"self-esteem" (p.004), and | |

|

"ability to love" (p=.031). |

Figure 44 provides and overview.

* 0-60 = T value

There were no significant mean differences (rank-variance analyses) on the SCL-90-R sub-scales. Direct comparison showed that participants without social support evinced significantly higher scores (p=.041) with regard to the characteristic of "depressiveness" (T=71.3; standard deviation 10.3) than participants with "sufficiently present" social support (T=60.9; standard deviation 11.0).

Sexual self-concept rank-variance analysis revealed large mean differences between participants with no pedosexual experiences (N=21), those with previous pedosexual experiences (N=43), and those with current pedosexual experiences (N=8) on the sub-scales of

|

"sexual self-respect" (p=.008), | |

|

"sexual depression" (p=.043), | |

|

"sexual clarity" (p=.004), | |

|

"sexual self-sufficiency" (p=.032), and | |

|

"sexual satisfaction" (p=.029). |

Participants who were currently living in a pedosexual relationship attained significantly higher scores than, respectively, participants with no pedosexual experience, or those with pedosexual experience in the past, in the sub-scale of "sexual self-esteem" (p=.017; p=.024) and "sexual satisfaction" (p=.017; p=.019).

Compared with participants in current pedosexual relationships and those with previous pedosexual experiences, participants with no pedosexual experiences had

|

higher scores on the "sexual depression" sub-scale (p=.022; p=.068) and | |||||

|

lower scores on the sub-scales of

|

The self-image of functional social potency showed that participants with no pedosexual contacts had significantly lower scores on the "communicability" sub-scale (p=.026) than participants who were currently living in a pedosexual relationship. Participants without pedosexual contacts attained lower mean rank-positions than the [87] other two groups on all of the SSF sub-scales. However, aside from the above mentioned exception, the inter-group differences were not great. Figure 45 provides an overview.

* CoCo = Consciousness of Control over ...

** C = Consciousness ...

*** 0 - 150 = Mean SSF

The mean values of the three groups for the "self-efficacy" characteristics were in the average range. Participants without pedosexual contacts showed significantly higher scores (stanine=5.8; standard deviation 1.8) on the "public self-attention" sub-scale (p=.007) than participants with pedosexual experiences in the past (stanine=4.3; standard deviation 1.9).

In comparison with participants who had had pedosexual contacts in the past, participants without pedosexual experience attained lower mean scores on the "carefree-ness" TPF sub-scale. (p=.034). On the TPF sub-scales, there was a trend in the direction of (still) average T-values for the two groups with pedosexual experiences (previous, current) and a tread in the direction of below-average T-values for the no pedosexual contacts group. However aside from the above-mentioned exception, the differences between the groups were not significant.

On the SCL-90-R sub-scales it was shown that participants with no pedosexual experiences had higher scores than participants who were currently living in pedosexual relationships or those who had had pedosexual contacts in the past. Rank-variance analysis indicated significant differences with regard to the sub-scales of

|

"duress" (p=.016), | |

|

"anxiety" (p.014), | |

|

"psychoticism" (p=.019), and the | |

|

"PSDI" (p=.029). |

Participants with

pedosexual experience (previous, current) did not differ significantly

from each other on the SCL-90-R sub-scales. Figure 46 provides an

overview.

[88]

| Som | Somatization | Agg | Aggressiveness |

| Dur | Duress | Pho | Phobia |

| Ins | Insecurity with social contact | Par | Paranoia |

| Dep | Depressiveness | Psy | Psychoticism |

| Anx | Anxiety | Glo | Global severity index |

| * 0 - 80 = T value | |||

With regard to the sexual self-concept, the self-image of functional social potency, and self-attention, there were no significant differences, in the U-test, between users (N=62) and non-users (N=10).

Users of pornographic images attained significantly higher (average) scores than non-users in the TPF's "self-esteem" sub-scale, (p=.027). No significant differences between the two groups were found on the SCL-90-R sub-scales. The greatest (still not significant) differences were on the sub-scales of "paranoia" (non-users T-65.1; users T=59.1) and "insecurity with social contact" (non-users T=65.5; users T=58.0).

Participants were subdivided into three groups:

|

the sexually abused in childhood group | |

|

the group with "agreeable" pedosexual contacts as children with adults (N=9) and | |

|

the group of those not approached pedosexually by adults during childhood (N=58). |

Those with pedosexual contacts retrospectively evaluated as "neutral" were included in the sexually abused group because "neutral" is seen as an unclear and dubious category, and because it is generally assumed that it is difficult for persons who have experienced serious, boundary violations to be able to admit to them.

There was a meaningful difference between the

groups on the TPF sub-scale of "behavioral control" (p=.018).

There was a trend in the direction of smaller (non-significant) T-values

among the sexually abused group than in the other groups. Figure 47

provides an overview.

[89]

* 0 - 60 = T value

Significant differences between the groups were observable on the SCL-90-R sub-scales. The sexually abused group evinced above-average T-values on nearly all of the sub-scales. Figure 48 provides an overview.

| Som | Somatization | Agg | Aggressiveness |

| Dur | Duress | Pho | Phobia |

| Ins | Insecurity with social contact | Par | Paranoia |

| Dep | Depressiveness | Psy | Psychoticism |

| Anx | Anxiety | Glo | Global severity index |

| * 0 - 80 = T value | |||

In the U-test, there were no significant differences between the group with "agreeable" retrospectively-evaluated pedosexual experiences with adults during their own childhoods and the group with no pedosexual contacts with adults during their own childhoods.

Significant differences between the group that had been sexually abused in childhood and the group that had not been pedosexually approached by adults during childhood were present in the following sub-scales:

|

"somatization" (p=.030), | |

|

"insecurity with social contact" (p=.004), | |

|

"depressiveness" (p=.019), | |

|

"anxiety" (p=.035), | |

|

"aggressiveness" (p=.021), the | |

|

"global severity index" (p=.010), and the | |

|

"positive symptom distress index" (p=.012). |

[90] Significant differences between the group with retrospectively positively-evaluated pedosexual contacts and the group with retrospectively negatively- or neutrally-evaluated pedosexual contacts were discernible on the following sub-scales: "insecurity with social contact" (p=.O21) and "aggressiveness" (p=.025).

(Presentation of the Associations Between Self-Concept Characteristics, Feelings of Being Under Stress, and Sense of Well-Being)

Step-wise multiple regression analyses were conducted. The predictor variables represented the entirety of the employed questionnaire scales for the individual self-concept spheres. The predictor variables of the individual self-concept spheres were set against the central criteria variables of "mental health" and the "global severity index". Multi-collinearity problems and suppression effects were considered and addressed in the calculations. Only the central results are presented. Table 14 gives an overview of, the associations between self-concept characteristics and "mental health".

Model |

Self-concept sub-scales (chi) |

Beta |

R |

Corrected R2 |

| Model 1 | Sexual depression | - 0.575 | 0.575 | 0.321 |

| Model 2 | Sexual depression & sexual self-respect |

- 0.411 0.399 |

0.680 | 0.447 |

| Model 1 | Consciousness of control over the environment | 0.775 | 0.775 | 0.593 |

| Model 2 |

Consciousness of control over the environment & Consciousness of self-control |

0.614 0.284 |

0.809 | 0.643 |

| Model 1 | Public self-attention | - 0.377 | 0.377 | 0.130 |

| Model 2 | Public self-attention & private self-attention |

-0.486 0.255 |

0.442 | 0.17 |

In terms of the sexual self-concept, the "sexual depression" variable accounted for 32.1% of the variance with regard to "mental health". It was negatively associated with the sense of well-being.

When "sexual self-respect" was considered as a predictor variable in the regression model, 44.7% of the variance in the sexual self-concept sphere vis-a-vis "mental health" was able to be jointly accounted for. Moreover, using bi-variate correlations, a series of statistically significant associations between "mental health" and various MSSCQ sub-scales were able to be demonstrated.

The four Self-Image of Functional Social Potency sub-scales correlated positively with the sense of well-being. In the regression model, the "consciousness of one's control over the environment" variable [91] accounted for 59.3% of the variance, with regard to "mental health". "Consciousness of one's control over the environment" and "consciousness of self-control" jointly accounted for 64.3% of the variance.

As to the components of self-attention, the regression model showed that "public self-attention" accounted for 13.0% of the variance with regard to "mental health". "Public self-attention" and "private self-attention" jointly accounted for 17.1% of the variance. In the bi-variate correlations, it was able to be shown that "public self-attention" was actively associated with "mental health" (r=.380; p=.864), and for the most part correlated with other TPF variables.

On the other hand, "private self-attention" evinced a nearly null correlation with "mental health" in the bi-variate correlations (r=.021; p=.864) and, with the exception of "forgetting of oneself", did not have statistically significant associations with the TPF health-related sub-scales. "Public self-attention" and "private self-attention" correlated negatively with the "forgetting of oneself" sub-scale.

Table 15 provides an overview of the association between self-concept characteristics and the "global severity index."

Model |

Self-concept sub-scales (chi) |

Beta |

R |

Corrected R2 |

| Model 1 | Sexual depression | 0.654 | 0.654 | 0.419 |

| Model 2 | Sexual depression & sexual self-concept |

0.565 - 0.215 |

0.683 | 0.450 |

| Model 1 | Consciousness of self-control | - 0.606 | 0.606 | 0.356 |

| Model 2 | Consciousness of self-control

& consciousness of control over environment |

- 0.456 - 0.314 |

0.666 | 0.423 |

| Model 1 | Public self-attention | 0.334 | 0.334 | 0.09 |

In the area of the sexua1 self-concept, the "sexual depression" variable accounted for 41.9% of the variance with regard to general feelings of being under stress. When "sexual self-respect" was considered as a predictor variable in the regression model, the two combined were able to jointly account for 45.0% of the variance with regard to the "global severity index" in the sexual self-concept area. Moreover, the use of bi-variate correlations revealed a series of statistically significant associations between the "global severity index" and various MSSCQ sub-scales.

The self-image of Functional Social Potency sub-scales correlated negatively with feelings of being under stress. The "consciousness of self-control" variable accounted for 35.6% of the variance with regard to the

|

"global severity index", | |

|

"consciousness of self-control" and | |

|

"consciousness of one's control over the environment" |

jointly accounted for 42.3% of the variance.

As to the components of self-attention, the regression model showed that "public self-attention" accounted for 9.9% of the "global severity index" [92] variance. The statistical influence of the "private self-attention" sub-scale is too small to support an expanded regression model. In the bi-variate correlations, it was able to be shown that "public self-attention" had a statistically significant, positive association with the "global severity index" {r=.319; p=.007). On the other hand, "private self-attention" bore almost no relationship to the "global severity index" (r=.030; p=.803).

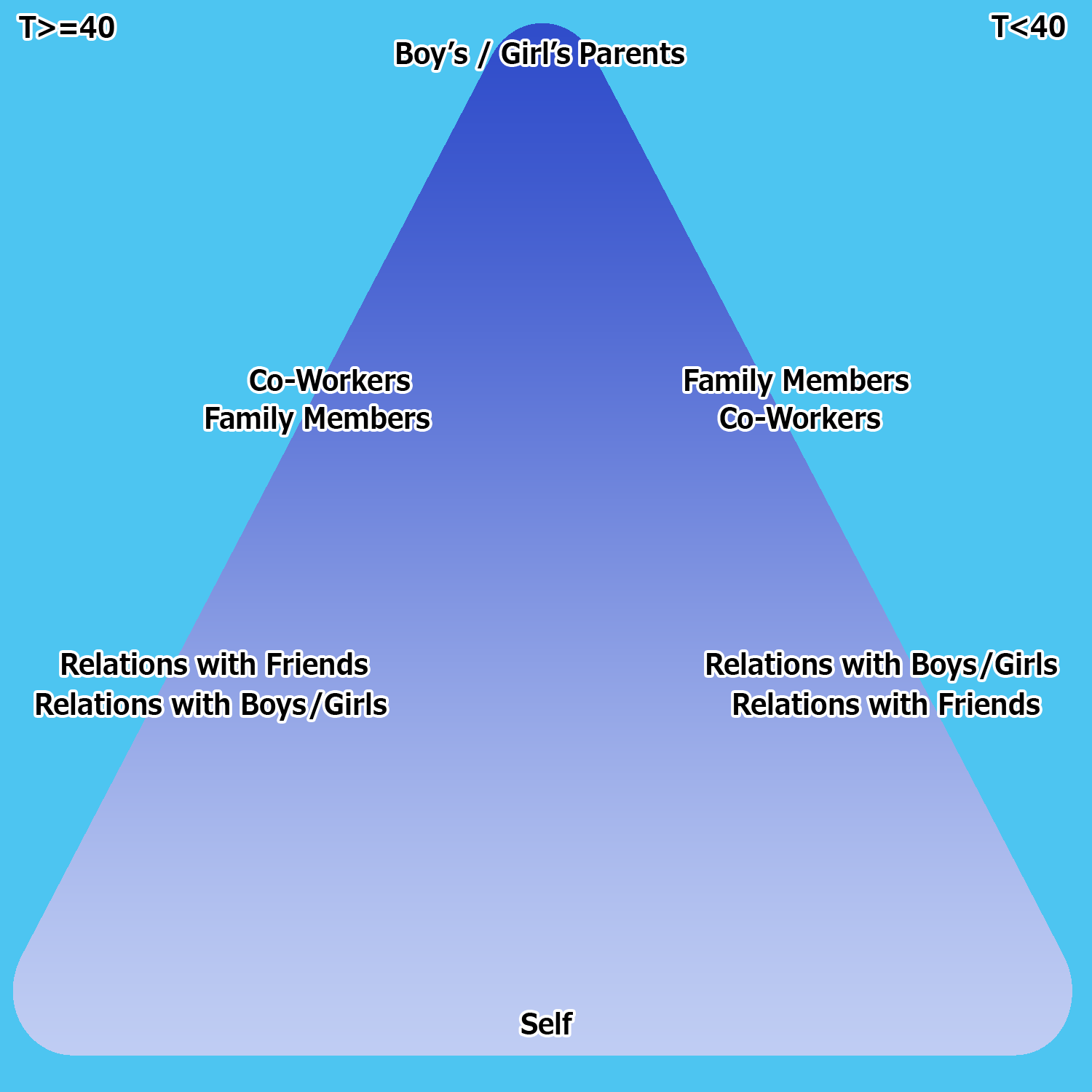

When asked about the importance of particular life-spheres, participants with average or above-average scores on the "mental health" sub-scale (N=31), compared to participants with below average scores on this sub-scale (N=37), yielded the following rankings:

The "friends" sphere was the most salient for both groups. Participants with average or above-average scores, on the "mental health" sub-scale emphasized the "work" sphere significantly more strongly (p=.015) than respondents with below-average scores on the "mental health" sub-scale.

"Sexuality and partnership" was emphasized as important by both groups, occupying the third rank-position. Among those participants with lower health scores, the leisure-time sphere was also of particularly great importance. The areas of "personality" and "health" occupied mid-level rank-positions. Both groups ascribed less importance to the "family" arena and the "material sphere", with the higher health-scores group giving greater weight to the material sphere (p=.015).

When participants were asked about the areas in which they experienced the most severe conflicts surrounding their sexuality, respondents with average or above-average scores on the "mental health" sub-scale, compared to participants with below-average scores on this sub-scale, yielded the following rankings:

[93]

Both groups experienced the strongest conflicts in the relationship with the child's parents, and the smallest, in reference to their own selves. The "co-worker" and "family" sphere involved a high potential for conflict. There were smaller conflict-potentials in the relationship with the boy or girl in question as well as in relationships with friends.

In an enclosed letter, one participant describes the potential for conflict inherent on his own situation:

"This social hatred is, for me, a constant presence. I cannot, for example, just sit down, relax, and watch TV like any 'normal' person does . . . for example, shows like 'Only Love Counts', where the love between two people is praised as the most beautiful and the most magnificent thing. I feel that my love for the boys is also the most beautiful and the most magnificent thing. But I know that I am pretty much alone in this view.

The same people who sit in front of the TV with a handkerchief, weeping with emotion over 'Only Love Counts', would be consumed with fury upon encountering my own views on love and affection – and I would be done for. I have no more chosen my own inclination than a straight or gay person can choose his. But I have to live with it, and it is a living hell. I personally am able to accept my inclinations because I'm certain that I'm not harming anyone; and even if all the prejudices are true, there is no way that I could ever do to a child what society has done to me."

To the question, "What attempts have you made to adopt a different (sexual) lifestyle?",

|

51 participants (70.8%) responded that they had in fact made attempts, in the past, to take up a different (sexual) lifestyle (98 were named overall). | |

|

Thirteen participants (18.1%) declared they had made no such attempts in the past. | |

|

Nine participants (12.5%) left this question unanswered. |

Table 16 provides an overview of the attempts made. [94]

Men-

|

||

| Sexual contacts and attempts at rels. with adults | 37 | Sex. cont./rels with - women (18) - women & men (10) - men (9) |

| Sublimation | 15 | - Mult. interests, volunt., religion (9) - marriage & their own children (6) - work in child & youth area (3) |

| Suppression / repression of one's sexuality | 11 | - suppression / repression of sexuality (8) - attempts at re-directing sexual fantasies toward adults (3) |

| Hope & health through therapy | 11 | - Counseling & psychotherapy (11) |

| Suicide attempts and self-isolation | 9 | - Suicide attempts & complete self-isolation

from world, esp. children (8) - withdrawing from pedo-scene (1) |

| Living out one's sexuality legally | 8 | - focusing on sexual contactss / rels. with

teenagers (16-18 years old) - (7) - Masturbation (1) |

| Distraction | 7 | - Via work & occupation (5) - Joining the army (2) |

The mean agreement between the two independent raters, across all categories, amounted to 95.1%.

A major portion of the respondents gave reports of – mostly in the distant past – failed and frustrating attempts to establish sexually satisfying contacts and partnerships with adults. These pedophilic men frequently made the statement that through sexual contacts with adults, they hoped to awaken their supposedly latently-present heterosexuality or homosexuality. The sexual relationship attempts were directed exclusive1y towards women, exclusively towards men, or towards both genders. Sexual contacts/relationships with women were most often reported.

The sexual experiences with adults were assessed in very different ways. There were some research participants whose sexuality with adults was possible only under the influence of alcohol. Frustrating brothel visits and [95] failed attempts at establishing partnerships through matchmakers were occasionally mentioned. On the other hand, other participants reported short- or even quite long-term homosexual relationships.

The respondents mentioned some quite varied efforts at sublimation.

|

Some attempted -- through multi-faceted interests, volunteering, or making the most out of spirituality -- to shift their sexual orientation away from being the centerpiece of their lives. | |

|

Others (almost exclusively older participants) sought salvation in marriage and families of their own. | |

|

Yet others, on the other hand, consciously pursued volunteer work in the child and youth arena. | |

|

Some respondents made the statement that they used volunteer work in the child/youth area in order to get close to beloved and desired boys and girls, as a kind of substitute for a sexuality that could not be lived out in a legal manner. | |

|

There were also research participants who totally isolated themselves from the world in general and children in particular. They rarely hung around streets and locales where they might encounter children. They went shopping only by car, or had a residence that faced away from the street. |

Particularly due to suicidal ideation, depression, and anxiety disorders, many respondents have gone into psychotherapy. A few respondents asserted that at the beginning of the therapy, they held out hope of changing their sexual orientation. Some of these pedophilic men have tried, in experimental personal attempts, to steer their masturbatory fantasies towards men and women (using pornography). None of the participants in question have, however, been successful in their efforts.

There were also pedophilic men found who frequent the gay scene, attempting to focus their sexuality on the legal age-range of 16-18. According to participants' statements, making the most of their "gay side" met with "quite variable" success.

Two men made unsuccessful attempts at repression, in which they voluntarily joined the army because they believed that would train them to have "the necessary severity towards themselves". Others distracted themselves through overwork. In isolated cases there was the hope for a "super-career" that was supposed to help distract them from their own sexuality.

Seventy-one participants (215 comments overall) responded to the question: "Who or what has, in the past, helped you to deal with your sexual orientation?"

Table 17 provides an overview of the sources of assistance received. The mean agreement between two independent raters, across all categories, amounted to 92.7%.

Comments |

|||

N |

% |

||

| Friends & acquaintances | 75 | 34.9 | - (40) Ped. friends, same ideas & feelings - (32) Non-ped-friends - (3) Others with understanding |

| Contacts with the pedo-scene | 37 | 17.2 | - ( 21) Self-help groups - (16) Internet chatrooms/forums |

| Professional help & family members | 44 | 20.5 | - (36) Counseling & psychotherapy - (5) Family members - (1) Clergy - (1) Attorny |

| Factual information | 18 | 8.4 | - (18) Specialized literature on the subject |

| One's own self & God | 17 | 7.9 | - (8) Mult. creative interests & personal

growth - (5) Spirituality & religiosity - (4) Belief in oneself |

| Boys & girls | 17 | 7.9 | - (9) Rel. with young boy/girl-friend - (4) Associating with children & youth - (4) Legal & illegal child pornography |

| Miscellaneous | 7 | 3.3 | - (4) No one - (3) Other |

[96] For a major portion of the pedophilic men, conversations about their sexuality with friends were the single most important resource. Respondents typically experienced interactions with pedophilic friends or pedophilic acquaintances as being very helpful. Many research participants also gave reports of understanding heterosexual or homosexual friends.

"Coming out" to these very close (best) friends was described as being a great relief. This was a step that was carefully considered and weighed by most of the pedophilic men. In the questionnaires, as well as in personal conversations and letters, the research participants reported predominantly positive "coming out" experiences involving friends.

"The fact that people can come to see things a little differently is something I experienced again just a short time ago, when I 'confessed' to a long time friend what was going on with me. She interpreted it very positively, and now I feel better because I don't have to conceal it from her, and I can also talk with her about things and feelings that move or even bother me. I do not think that one would he able to change the minds of the masses anytime soon. But you can start with small steps, enlightening those whom you are able to trust, because you never know they will actually react."

(Excerpt from a letter enclosed by one of the participants.)

There was also, however, the occasional very negative experience in this area. The example of one enduringly negative experience will be presented at this point; in order to highlight the necessary weighing process as to whether and to what extent a pedophilically-inclined person can be open with those around him.

"I'd had a very close friendship with a boy and also with his parents for a couple of years. Although the boy would at times absolutely overwhelm me with sexual propositions (this truly was the case!), I always firmly rejected them, though this was often very difficult for me.

I did not want to leave myself open to prosecution, and I also did not want to abuse the trust of his parents under any circumstances.

The following thoughts were always going through my head: 'just don't make any wrong moves, don't do anything that I might get blamed for later on.' This was already becoming a nearly crippling fear for me.

At that time I had the admiration of everyone, because I was of course great with the kids, and naturally also because it was terrific that I had a first-rate rapport etc. with boys. But inside I was seething with anger at the thought of how these same people would react if they were to find out about my inclinations.

The discrepancy between my own feelings and society's point of view could not have been greater, something that was such an extreme burden on me that one day, I made the mistake of outing myself to some people.

Consequences:

|

reports to the police, | |

|

false accusations, | |

|

having my home searched, | |

|

arrest, | |

|

judicial inquest, | |

|

etc. |

And of course there was no way out of it. Although the proceedings were suspended; but my life was ruined. I was outed to everyone around me, and the boy's parents, with whom I had been friends at the time, severed all contact with me. I never saw them again, and it's also been years since I last saw the boy.

With one stroke I had lost all of the people who had loved me and were important to me at the time, and I can't describe how much I missed the boy then, and he me, although less than I did him.

Since then, I have no longer felt like establishing a relationship, or even a close friendship. More and more I find myself withdrawing from and avoiding people who are seeking friendship with me, because under no circumstances would I care to go through something like that a second time. In any event; because I have in fact already suffered very severe depression, which was absolute hell for me at the time, I don't know if I could go through it again."

(Excerpt from a letter enclosed by one of the participants.)

Contact with the pedo-scene was mentioned by many of the participants as important for dealing with their own sexuality. Above all, the self-worth-enhancing message of "You are not alone" was imparted by friendships and acquaintances with those of like mind or through corresponding Internet forums. For some participants, self-help groups had been a jumping-off point for "outing" themselves -- really for the first tine -- through direct contact with other people, forsaking the fears and problems related to their sexuality, and for establishing friendships.

Thirty-six participants cited professional help as an important source of assistance. Psychotherapists were among those who the participants found to be somewhat helpful; mentioned more often, however, was S. Tanner's anonymous counseling center in Switzerland, and, more generally, the counseling team affiliated with it.

Two comments referred to members of the clergy, and one mentioned a lawyer.

Those affected also found family members to be somewhat helpful (five comments). These usually involved the mother (e.g., "liberal attitude regarding sexuality"), and in one case, a brother. Fathers were not mentioned as supportive, helpful persons.

This was also underlined in some of the personal conversations with research participants, whose personal experiences were that the mother, above all, was more likely to demonstrate an understanding of their sexual orientation than the father was. The fathers' reactions, to the extent that they were let in on it, were oftentimes rather rejecting and dismissive.

("Just get to work and look for a wife, keep at it," quoted from a personal conversation with one participant).

Oftentimes, however, this is too much for both parents, who then disassociate themselves from their son. Other parents remained in contact with their son, but still worried that this would leave him vulnerable to prosecution.

Many participants also found reading specialized scientific literature on the subject to be helpful, naming authors such as Bornemann and Brongersma (e.g., "Loving Boys" I & II ).

For some participants, assistance from self-help groups comes in the form of a strong personal belief in one's own personhood. Others, on the other hand, declare that they find support in spirituality and religiosity. Many successfully avoided -- through the establishment of multi-faceted interests and hobbies -- allowing their own sexuality and its attendant problems to become the focal point of their lives.

Some participants report that their relationship with their young friend has helped them, and that through this relationship they have been able to receive feedback and acknowledgment. The participants also declared that they found frequent interaction with children to be a substitute for un-lived-out sexuality.

Four participants experienced as helpful the masturbatory use of legal and illegal child pornography. Seven comments comprised a miscellaneous category. Four participants [98] stated that on this point they had not received any assistance. Three comments were categorized as "other" (e.g., "anti-depressants").

The responses from 19 participants currently in psychotherapy -- as well as two participants who had been in psychotherapy previously -- to the question, what goals would they like to achieve with the assistance of a psychotherapist, were able to be combined into four basic content areas. Only one participant was unable to name any therapeutic goals. Another emphasized the relief experienced via therapeutic conversation. Multiple aims could be mentioned (38 named overall). Table 18 provides an overview. The mean agreement between two independent raters amounted to 87.2% across all categories.

Goals of psychotherapy |

Mentions |

Specific areas |

| Improvement of general capabilities | 12 | - (6) General life-mastery & problem-solving

ability - (3) consciousness of self & social competence - (3) Consistency & structuralization |

| Finding meaning & contentment | 9 | - (5) Search for meaning and identity - (4) Balance & contentment |

| Overcoming or dealing with affective disorders | 7 | - (5) depression & suicidal ideation - (2) Chronic anxiety & panic attacks |

| Dealing with one's own sexuality | 10 | - (3) Accepting one's sexual feelings - (3) Sexuality & day-to-day life - (2) Living crime-free / redirecting sexual activity - (2) Making peace with sexual abstinence |

"Improvement of general capabilities," the most frequently mentioned general goal, encompasses three specific areas.

|

Statements such as

belong to the

"general life-mastery competence" area. | |||||

|

Goals such as

represent the specific area of

"consciousness of self and social competence." | |||||

|

The area of "consistency and structuralization" encompasses responses such as

|

An additional central therapy goal of some of the participants was "finding meaning and contentment," which consists of

|

the search for meaning and identity spheres | |

|