Nanshoku,

the Japanese word for eroticism between adolescent and adult males, was

the longest lived and most public expression of same-sex affection

anywhere in the world. We recreate what it was like as we follow a

fictional samurai, Tsūsaburō, on his way to the kabuki. We

then describe the center of Tsūsaburō's Edo and present a

description of nanshoku in literature and art. Edo was the name for

Tokyo until the overthrow of the shōgun in 1868.

Ume yanagi sazo wakashu kana onna kana

(Plum and willow, boy or woman?)

— Matsuo Bashō

Edo, 1787

An unseasonably warm spring breeze rippled

the flags on the ritual washbasin at Yushima Hill's Shintō shrine.

Visitors crowded the grounds, enjoying the fragrant plum blossoms. Tsūsaburō

paused to read the names on two of the banners: Bayō from the

Kabukiya and Utagiku from the Tateya. Utagiku...

Chrysanthemum-song, a lovely name for a boy. The young samurai didn't

know the brothel where Utagiku worked, but he had been to the Kabukiya.

This morning he was headed to a real kabuki performance. He knelt

briefly in front of the basin, praying for an engaging performance as

well as Utagiku's fortunes.

On his way out of the temple, Tsūsaburō

passed the telescopes through which people gazed down at the sprawling

city of more than a million, at the Ryōgoku Bridge arching

gracefully across the Sumida River and the bay beyond. He would soon

walk by the bridge en route to the theatre in the Yoshi-chō.

Yoshi-chō and Yushima Hill had been two of Edo's largest nanshoku

districts for more than 150 years. Each had dozens of teahouses,

brothels, hotels and bathhouses at which boys and men met.

Tsūsaburō threaded his way

through narrow streets, tracking his progress by the guardhouses placed

at 120-meter intervals. He passed blocks of cramped commoner housing.

Nameplates on the gates to the alleys behind them announced plasterers

and palm readers, doctors and calligraphy teachers. The scenery changed

dramatically as he reached the large plaza fronting the bridge. It was a

crossroads for all Edo. Banners festooned the tall buildings near the

water's edge, advertising massage healers and carnival attractions,

including a charcoal eating ostrich and a porcupine from the mountain

wilds of Tanba.

Vendors peddled loquat leaf broth and sushi vinegar

rice; merchants sold Dutch cloth, dumplings and inari fritters. A

cacophony of strings, drums and flutes accompanied their cries. People

of all stations and ages were shopping, sightseeing or hurrying through.

They stood elbow-to-elbow along the Ryōgoku's wooden balustrade

watching the busy river traffic.

Tsūsaburō noticed the man deftly

wielding a pair of enormously long chopsticks to hand the sweet chilled

agar-jelly treat tokoroten up to a customer on the second floor of a

building. But it was a youth trying his skill at a blow-dart booth who

caught his eye. He was a maegami, a boy with forelocks, thus about 13 or

14. The lad noticed Tsūsaburō's expensively tailored kimono

and the two swords – the long katana and short wakizashi – denoting

his noble status.

Gracing him with a grin, the boy urged Tsūsaburō

to join him, suggestively tapping a dart into the blowgun's long tube.

Tsūsaburō merely smiled. Maybe he would like to see a sumo

match in Honjo, just across the bridge. Better still, Tsūsaburō

thought wryly, take him to the Fukiya-ga-hama (Blow-dart Beach), a

well-known male brothel. But as attractive and seemingly willing as the

youth was, kabuki starts early and Tsūsaburō did not want to

miss the scene in which Hanai Saizaburō would make his entrance. He

gave the lad a shrug. Some other time perhaps.

Arriving at the Yoshi-chō, the samurai

came to the Nakamura-za theatre. Lanterns swung from its red and green

striped facade. A prominent roof tower with a black gingko leaf curtain

marked it as one of Edo's three large kabuki playhouses. Long vertical

signboards listed the day's events, including the play he had come to

watch, Chikamatsu's drama Shinjū yoigōshin (Love

Suicides on the Eve of the Kōshin Festival). It was a popular work,

its theme taken from an event which had occurred only weeks before its

premiere. The signboards were scarcely necessary; on a wide raised stage

before the entrance sat the kido geisha, raucous barkers pointing their

fans at passersby, mimicking the actors' voices.

Above them a poster

read "house full" but Tsūsaburō was known to the

ticket seller. Though samurai were not allowed to attend kabuki,

theatres routinely looked the other way. Within moments, 4000-mon ticket

in hand (roughly 70 euros), he was making his way to a box in front of

the galleries overlooking the hanamichi (flower path), the runway and

secondary stage on which the performers entered the cavernous hall.

It was a good place to see and be seen,

almost at eye level with the actors. To his right, Tsūsaburō

noticed a lattice screen on the sides of a box above the pit, shielding

its occupants – a high-ranking samurai or perhaps a daimyō

(domain lord) – from the audience. The first act was already underway,

spectators eating, drinking and commenting on the performance.

He took his spot in time to watch the actor

playing Hanbei, a samurai who had fallen to the status of a merchant,

decide which of three noblemen was worthy of the love of his younger

brother, the novice samurai Koshichirō. Hanai Saizaburō would

play Koshichirō. Tsūsaburō wondered if the young actor

would live up to his billing.

At that moment the boy entered along the

hanamichi. Tsūsaburō caught his breath. Hanai was as beautiful

as he had heard. The yarō hyōbanki (actor critiques) hawked in

the theatre district had not exaggerated. He was listed as one of the

highest earning wakashu-gata (adolescent actors). At 15, he had the

presence of an older performer; his refined manner, said the hyōbanki,

made the movements of other wakashu-gata look like those of untrained

falcons.

Hanai walked down the hanamichi in white

death robes, softly singing an aria in a haunting voice. The plucked

strings of a shamisen provided a plaintive accompaniment. Women and men

in the audience winked at him, wordless offers of one-night

companionship. Hanai's eyes flitted impassively over their faces,

including Tsūsaburō's, paying them no heed. In this he was

following the nō master Zeami's dictum that the actor turn his face

in the direction of the audience but never gaze directly at it, not even

at nobility.

This was common in the more stately nō, Tsūsaburō

knew, but not in kabuki, where actors would often pose and fix audience

members with an uso (special look) in the hope of meeting after the

performance. The boy had remarkable poise.

On the main stage, Hanbei placed a pair of

unsheathed swords on a small offering table in front of his brother's

suitors. Their half-meter long blades were equally suited for combat or

seppuku (ritual suicide). He sternly told them whoever wanted his

brother's hand must be prepared to join him in death. As the play's

narrator observed that the boy "maintains nanshoku's highest

principles," Hanai moved wordlessly toward the table. He sat by it

and looked from the deadly weapons to each of the men.

Tsūsaburō recalled a passage

written 100 years earlier about the young Osaka actor Uemura Tatsuya. It

was from the brush of the novelist Saikaku: "The distant sky so

frightening! How greatly he resembles the beautiful pet boys so loved by

lords of ancient times. The incense fragrant in his hair... selected by

moonlight... That long and slender figure like the bending willow reed:

what could be more replete with fascination?" Uemura might have

been beautiful, Tsūsaburō mused, but what boy could have had

Hanai's feline grace?

His pulse quickened at the feral spirit he thought

might underlie the youth's calm demeanor. Hanai was beyond beauty.

Surely he was already the companion of some high-ranking lord, perhaps

even now in the auditorium watching his younger lover.

The three samurai shrank from the sight of

the swords and the sound of Hanbei's harsh words. But not the young

footman Koichibei. Making a dramatic entrance, dressed in a plain blue

commoner's kimono, he declared himself ready to die for the boy's love.

Koichibei strode over to the table and picked up a sword. It glittered

in the sunlight streaming in under the theatre's open eaves. Hanai moved

close to him in readiness.

The audience fell silent. Koichibei began to

bring the sword down, but suddenly Hanbei stayed his arm, declaring

Koichibei's heart to be the most sincere. "May you always remain

close," said Hanbei as he sanctioned their vows of unity and

fidelity. As the man and boy embraced, the narrator commented,

"Deep solid blue against immaculate white-a brotherhood of

unblemished purity."

At the end of the act, Tsūsaburō

watched as Hanai walked back along the hanamichi. Passing Tsūsaburō's

box, the boy locked eyes with him and nodded almost imperceptibly, a

hint of a smile on his lips. The samurai felt his heart skip a beat.

Ignoring whispered comments by those around

him, Tsūsaburō made his way to the adjoining shibai-jaya (a

teahouse used to meet actors). As he left the hall, he reflected on the

audience's fascination with the performers' physical beauty and

sexuality. Perhaps the actor's most difficult art is displayed after the

straw mats (curtain) came down, he thought. The actor must manufacture

that uso for one or more customers again and again until dawn. Tsūsaburō

flushed, thinking of how Hanai looked at him, and hurried into the

shibai-jaya.

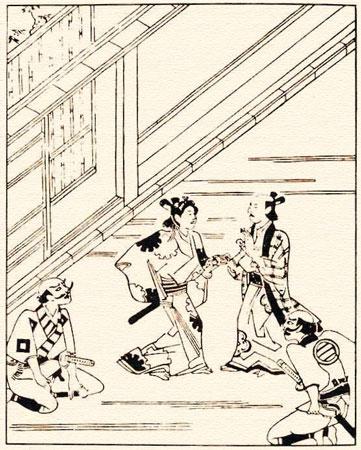

Boy Actor and Lover (anonymous, 1643)

Edo in real life

Three of Edo's better known nanshoku areas

were Yushima Hill, Kobiki-chō and Yoshi-chō. The latter two

were also theatre districts. Kobiki-chō was in what today is the

Ginza. Yoshi-chō survives as a block name in the area now called

Nihonbashi. The Fukiya-ga-hama, the brothel to which Tsūsaburō

imagines taking a youth he sees, was popular, its name punning that of

the Fukiya-chō block in the Yoshi-chō. The establishments

Kabukiya and Tateya, whose names appear on the banners Tsūsaburō

notices at Yushima Hill's Shintō shrine, may have been fictitious.

Utagiku (chrysanthemum-song), the name on one of the banners, would have

been read as that of the boy prostitute who had made an offering at the

shrine; chrysanthemum was a symbol for the anus.

From not long after the construction of the

Ryōgoku Bridge in 1659 and for the next 200 years, the

carnivalesque atmosphere of the large plaza on the Nihonbashi side of

the span symbolized the heart of Edo much as Times Square did New York

City during the 20th century. Blow-dart booths of the type Tsūsaburō

sees are depicted in illustrations from the period (the goal being to

hit a string which would unhook to release a prize). Sumo matches are

still held on the other side of the Sumida River.

The authorities created the plaza (a hirokōji,

or broad open space) as a firebreak, probably not realizing it would

become the city's foremost area of popular amusement. On the hirokōji

proper, the many lively small merchant and carnival stalls concentrated

the popular energy – Edo's 'libidinal economy', in the words of J.

Lyotard – while the vista of the river and open fields on the other

side of the bridge presented a sense of freedom. The contrast between

the sight of the closed-in stalls and the open spaces of the river and

countryside is exemplified in the paintings and prints called ukiyo-e

which depict Japan's 'floating world', or the pursuit of pleasure.

Jilly Traganou observes that many ukiyo-e

employ techniques which blur the typically Western distinction between a

map and a picture. Ukiyo-e present a mosaic of loosely connected scenes

rather than an integrated view based on a photograph-like visual

perspective. In this it exemplifies the medieval aesthetic of

resonances, which reached its peak in the haikai linked verse of

the poet Bashō. Perhaps nowhere would the ukiyo-e aesthetic have

been more evident in real life than on the hirokōji fronting the Ryōgoku.

If any location could be said to have marked the center of Edo Japan's

floating world it may have been this.

The authorities banned samurai from the

kabuki because of incidents like that in Kyoto in 1656, when a samurai,

jealous over the affections of a boy actor, provoked a swordfight in a

theatre box. By the mid-1600s, not long after its establishment, kabuki

had become a locus of boy prostitution. Kabuki was engaged in a running

ideological battle with the state. Writes Steven Heine, it constituted

'a perpetual anti-structure ... that represented the antithesis and

rejection of the puritanical, Japanese-adapted Confucian values endorsed

by the shōgunate.' As members of the ruling class, samurai were

expected to uphold these values, which allowed for boy love but not

attendance at entertainment for the lesser classes. Many samurai partook

of both; hence the screened boxes mentioned in the story.

Although by Tsūsaburō's time many

nanshoku-oriented establishments were centered around the kabuki,

nanshoku, as much as part of life as sunlight, would have been visible

everywhere. This is unlike the gated, sometimes moated, heterosexual

pleasure quarters of the large cities, such as Edo's Yoshiwara. Very

likely men and male youths had more freedom of action with each other

than did men with women.

Given nanshoku's long history, it is little

wonder high officials in the late 1700s were astonished to learn that

Western countries severely punished male-male sex, even if the younger

partner was willing. After the overthrow of the shōgun, Japan

briefly had a law prohibiting same-sex practices. It banned anal

intercourse and was in effect from 1873 to 1880, when it was repealed

and an age of consent established at twelve, raised to thirteen in 1907.

Today there are age-of-consent laws at the prefectural level prohibiting

sexual relations with those under eighteen.

Literature and art

Nanshoku's evolution can be traced from the

medieval monasteries to the samurai and eventually to the merchant

classes in Edo, Kyoto and Osaka. Some of its earlier representations

include scroll paintings and chigo (acolyte) stories, such as the

14th-century Chigo Kannon Engi which poignantly depicts the

Buddhist concept of life's transience.

One of Japanese literature's great lovers

was Ariwara no Narihira, protagonist of the classic Ise monogatari.

As a boy he was the subject of what became a well-known love poem, 'Iwatsutsuji' (Azaleas on the Cliffs), written by an unknown priest in

the 9th century. Seven hundred and fifty years later, the shōgunate's

poetry tutor, Kitamura Kigin, compiled an anthology intended to show the

long tradition of idealized relations between male youths and men.

He

named it after the poem. Nanshoku was everywhere, observed Kigin. He

wrote in his preface that it '...plagues the heart of not only courtier

and aristocrat (this goes without saying) but also of brave warriors.

Even the mountain dwellers who cut brush for fuel have learned to take

pleasure in the shade of young saplings.'

Kigin may not have known his collection

came at the dawn of nanshoku's greatest flowering in literature and

arts, during the Genroku era (c. 1688-1710). Scholars compare Genroku to

the Renassiance for the number of brilliant works and the eagerness with

which the public consumed them. Three of Japan's most famous writers

were at the peak of their expressive powers: Ihara Saikaku, who

introduced the realistic novel to Japanese fiction, Chikamatsu

Monzaemon, whose dramas helped determine the nation's discourse on

loyalty and heroic virtue, and Matsuo Bashō, master of the linked

verse haikai.

Saikaku wrote perceptively about the love

of women (his first novel, Kōshoku ichidai otoko [The Life

of an Amorous Man, 1682], lampoons the Ise monogatari in part),

but nanshoku is present throughout his œuvre as it was in life. It

takes center stage in his collection of stories Nanshoku ōkagami:

honchō waka fūzoku (The Great Mirror of Male Love: the

Custom of Boy Love in Our Land).

It was a crossover work which the

Osakan hoped would attract samurai readers in fast-growing Edo as well

as his established audience of merchants and artisans in Osaka and

Kyoto. It succeeded at this, becoming a best seller on its publication

in 1687. Saikaku's sharply and wittily drawn characters are supremely

humane. They act on their desires in ways that are familiar today. In

their foibles and noble acts, their failings and successes, they allow

us to see something of ourselves in them.

Chikamatsu's Shinjū yoigōshin

(Love Suicides on the Eve of the Kōshin Festival), the play Tsūsaburō

attends, was one of his last works, premiering in 1722. It has been part

of the kabuki/jōruri (puppet theatre) repertoire ever since.

Chikamatsu's influence in Japan has been compared, justly, to

Shakespeare's in English-speaking cultures. Chikamatsu authored more

than 100 works, of which about half have been adapted for film and

television. He used nanshoku in the first act of Shinjū yoigōshin

to establish Hanbei's character as someone who chooses wisely from among

competing demands and who values love above life itself.

Hanbei's

younger brother Koshichiro was 15 or 16. As he matured, he would perhaps

take a boy lover of his own and probably a wife. The tie between him and

his older lover Koichibei would endure, each expected to give his life

for the other if need be. This was a samurai ideal, different from the

reality of the townsmen's mercantile world, where men – and some women

– bought the company of boy actors.

Nanshoku was depicted in erotica known as shunga

(spring pictures). Kitagawa Utamaro produced some of shunga's finest

examples. The expressions he gives people making love are breathtakingly

intimate. The government took mostly a laissez-faire attitude toward

regulating visual art. But one image earned Utamaro 50 days in manacles.

Machiba Hisayoshi (c.1803-4) is a colored woodblock print of the

ruler Hideyoshi leaning toward a pageboy, caressing the youth's wrist.

It was not the late shōgun's conduct which perturbed authorities

but his representation: pictures of high nobility were forbidden.

Shunga had its humorous aspects. Terasawa

Masatsugu's monochrome woodblock print Song (1770s) shows the boy

Sukejirō one night using his music practice to mask the sounds of

another, more pleasurable, pursuit, of which the artist leaves nothing

to the imagination. Unfortunately for Sukejirō, his parents are

light sleepers. They open the screen between their bed and where the lad

is sitting. With a bemused expression the father says, 'It's not often

he gets out his "devil-eyed horn",' while the mother

complains: 'He's at it again? He never takes his mind off sex.' Sukejirō,

looking peeved, asks them to 'Stop embarrassing me and let me just go to

bed.'

Nanshoku-themed works were popular well

into the 19th century. Kigin's anthology Iwatsutsuji was

published until 1849. Jippensha Ikku's 1802 Tōkaidōchū

hizakurige (Down the Tōkaidō on Shanks Pony, i.e., on

foot), a picaresque road novel, tells of the adventures of a man/boy

pair who, when the boy reaches adulthood, decide to quit their quarters

in Edo and explore Japan. Although not showing them having sex once they

begin their adventures, their relationship is central to the book, whose

preface consists of a series of nanshoku puns and whose characters make

nanshoku jokes throughout the novel. Tōkaidōchū

hizakurige was wildly successful, bringing its author fame and

spawning imitators as late as the 1850s.

The 20th century

United States Commodore Matthew Perry

steered his fleet of modern steam-powered warships into Uraga Bay in

1853. When he got close to land, he fired their cannon. The Japanese

stood on shore ready to repel the invaders. They were armed with muskets

and swords. They had never seen steamships. Perry's visit, ordered by

the U.S. to coerce the nation into signing unfavorable treaties, was as

much of a wake-up call for Japan as Pearl Harbor would be for the North

Americans 90 years later.

As Japan scrambled to industrialize, nanshoku

faded from public expression. Soon, following the new discipline of

Western psychiatry, it was condemned. A set of Saikaku's works was

banned in 1894. Most of the nanshoku-themed plays in the kabuki and jōruri

were dropped from the repertoire, including the first act of

Chikamatsu's drama described above. Many have been lost.

Westerners problematized

nanshoku. W. G.

Aston, a British diplomat whose 1899 survey of Japan's literary

traditions was the first in English, declared, 'The very titles of some

of [Saikaku's stories] are too gross for quotation.' His explanation:

their 'leading feature ... is of such a nature to debar more particular

description.' But Japan's reputation was noted approvingly by early

homosexual rights activists in Germany, notably Benedict Friedländer, a

member of Magnus Hirschfeld's Wissenschaftlich-humanitäres Komitee

(Scientific-Humanitarian Committee), and Edward Carpenter in England,

where, in 1911, he cited comments made five years earlier by Ferdinand

Karsch-Haack about Nanshoku ōkagami.

Some of Saikaku's

nanshoku stories were translated into French in 1927 and from French to

English in 1928. Even so, in 1960, Tōkaidōchū

hizakurige's nanshoku content was excised in an English translation

from Charles Tuttle; 12 years later, the preface to Saikaku's stories

published by the same firm called nanshoku's theme 'sordid'.

Present-day critics have not always

been sympathetic, as may be seen in a comment about Okumura

Masanobu's 'Sexual Threesome' (c. 1738). The woodblock handscroll,

displayed here, shows a man penetrating an adolescent girl

while holding the erect cock of an adolescent boy lying next to

her, perhaps as a prelude to penetrating the boy as well. As

late as 1995, a Japanese scholar characterized this as: '...a

fitting revenge for this girl who has seduced the boy. The man and

woman seem happy enough, only the boy is unfortunate.' As Timon

Screech observes, the scroll provides no evidence for this interpretation:

'...why is the boy "unfortunate" (fuun), and

wherein lies this "revenge"?'

This climate is changing. Several excellent

works in English have been published in the past 25 years. A 1995

issue of the Japanese journal Bungaku, 'Nanshoku no ryōbun:

seisa, rekishi, hyōsho' (The Domain of Male Love: Gender, History,

Representation), has more than a dozen articles embodying new critical

perspectives. The famed director Oshima Nagisa treats nanshoku frankly

in his 2000 movie Gohatto (Taboo), which is based on the chapter

'Maegami no Sozaburō' in Shiba Ryotaro's novel Shinsen-gumi Keppūroku.

In the West, male adolescent-adult

eroticism has been visible only at the cultural margins. With a very few

exceptions, it has not been openly celebrated since the poets of

Sephardic Spain, whose odes circulated throughout their society. Michael

Rocke documents the prevalence of male adult-adolescent relations in

Renaissance Florence. From tavern boys to Niccolò Machiavelli's son

Lodovico, Rocke says such relations were so widespread as to not be a

subculture. But though there was tolerance, the only cultural expression

came in the condemnatory sermons of churchmen like Savonarola. Given the

long and very public presence of nanshoku, perhaps more of its texts

will be recovered and translated.